Science & Engineering | Feature

3D Printing in the Classroom: 5 Tips for Bringing New Dimensions to Your Students' Experiences

Advice from a middle school science teacher who uses 3D printing to help students learn design, production and persistence.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 12/11/13

When the New Media Consortium Horizon Project identified the technologies that were expected to have a major impact on STEM+ education in the next several years, its group of education experts around the world identified 3D printing as coming to the forefront in the next two to three years. For some classrooms, that day has already arrived.

As "Technology Outlook: STEM+ Education 2013-2018" stated, 3D printing is relevant in teaching and learning as a way to enable "more authentic exploration of objects that may not be readily available" to teachers and students; it provides a means to let students handle "fragile objects," such as fossils and artifacts that can be fairly quickly prototyped and printed out; and it opens up "new possibilities for learning activities." What the report doesn't say but the students in Christine Mytko's middle grade science class will tell you is that 3D printing also lets kids learn how to endure adversity and persist in solving problems.

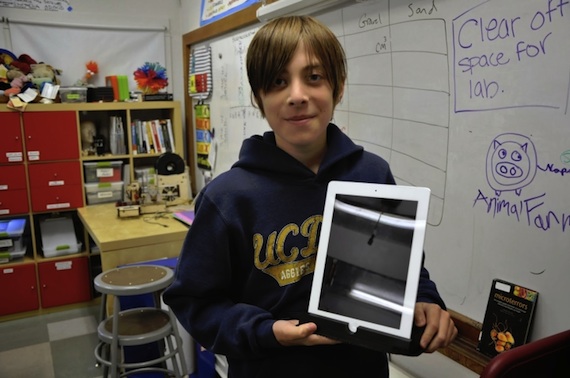

For example, there's Cole Compton, who has gone through numerous iterations in his attempt to design and print out an iPad stand. As documented in Mytko's blog entry on the topic, "The Epic iPad Stand Journey," Compton faced challenges in designing his stand (he shifted from SketchUp to Tinkercad), grappled with loose filament feed tubes on the printer (a binder clip eventually saved the day on that), dealt with a build plate that wasn't heating evenly (Compton adjusted the positioning of the model to print in a different position), tackled a spool of filament that kept getting pinched up (the class borrowed a spool coaster from another printer), ran out of black filament hours into the print (Mytko attempted to complete the print with another color of filament, but the transition didn't work), and encountered an uneven printing bed that forced the print job to be canceled yet again.

"There hasn't been a completely successful iPad stand. Something always goes wrong though some of them have come pretty close," Compton noted stoically. Along the way, he added, he has also become accustomed to the fact that sometimes even the best efforts fail.

Black Pine Circle School student Cole Compton holds a partially printed iPad stand. (Photo courtesy of Christine Mytko.) |

Mytko, who teaches at Black Pine Circle School, a private school in Berkeley, CA, is a life sciences teacher by training. She started an after-school club to introduce students to the "maker" mentality, applying practical skills to creative invention. That evolved into converting one of her science class days into "Maker Mondays," a double period with a focus on design and creation using programs such as Tinkercad, Makey Makey, and the 3D printers.

Here, Mytko and three of her students offer five tips for making the most of 3D printing in the classroom.

Let the Printer Be the Lesson

Mytko acquired her first 3D printer, a $300 single-color PrintrBot, after attending a maker fair. She acquired her second one, which came from MakerBot, in order to be able to print two colors at once. She picked up a second PrintrBot "because of a big discount" and was recently gifted a free Cube by 3DSystems.

Each of those printers comes with its own learning possibilities. "With the Cube," she explained, "I tell the kids it's more like a washing machine. You just press a button and it does [its job]. With earlier 3D printers you have to spend a lot of time making sure the screws are tightened, that the extruder nozzle isn't caught, that you've set all the settings for how fast the filament should be pulled through, for setting the temperature of the tray."

Those earlier printers have given her students ample opportunities to learn how to tinker and finesse a machine to get it to work right. Compton and a buddy would spend their lunch hours taking that first printer apart. There were days, noted Mytko, when she'd walk into her classroom, see the PrintrBot dismantled, and conclude it was "never going to go back together." But it always did. "Moving forward, kids may be able to get their designs printed faster and more efficiently with less failed prints, but they also lose some of the magic of working with the machine."

Consider the After-School Club Approach

The club allowed Mytko to develop "a small group of dedicated kids" who weren't afraid to tinker. "To sit at home by myself with that printer trying to learn how to use it would have been an incredibly frustrating activity," she said. ""But when you're surrounded by kids, they take joy in every little discovery we make."

A second benefit, she added, is that the club can solve problems and test gear out " before we're standing in front of a classroom of 24 kids, many of whom are not choosing to be there."

Admit You Don't Know It All

Your students will help you learn, Mytko said. "Be really honest," she advised. "I think teachers are used to being the experts in the classroom. We need to admit to kids when we're not the experts and ask them for their help in learning together. We approach the whole Maker Monday thing as a team effort."

Mytko acknowledged that while coming clean can be "academically humbling," it avoids the added embarrassment of having the kids "see right through that — especially at the middle-school level."

Besides, it forces students to take on the expert role for themselves. Now, when somebody is facing a specific task for the first time — printing in 3D, planning a project, setting the temperature on the printer — "there are two or three kids in each class period that know how to do this."

While that self-dependency is part of the maker philosophy, it also applies to 3D printing, Mytko said. "I have kids who are experts in certain areas. Cole has the most experience with the 3D scanning. I have other kids who are very quick on Tinkercad. Anytime somebody has a question about how to make rounded edges, I'll say, 'Go ask James.'"

And, she added, "We have our excellent co-worker, named Google. Often the solution is, 'Go ask Google.' The beauty of it is, somebody has already asked this question, and somebody else has already written down the answer somewhere."

Don't Grade the Results

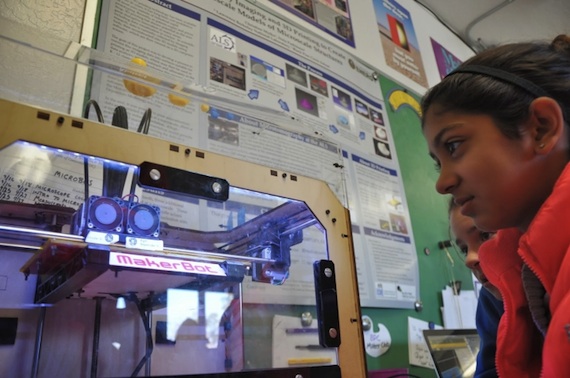

Seventh graders Inika Bhatia and Hayley Sullivan are working on a project together, a plastic picture frame that can be adjusted for multiple sizes of pictures. It's the first 3D object they've designed, and they expect the whole project to "take a very long time." Said Sullivan: "It's creative. And it's not graded. It could completely fail at the end, and you wouldn't be graded on it."

Students Inika Bhatia and Hayley Sullivan monitor a print job. (Photo courtesy of Christine Mytko.) |

In order to do the design, however, they're picking up experience in learning the metric system and practicing measurements. "If I were to hand them a worksheet asking them to do the same thing, they would enjoy it less," noted Mytko. "Now they have to use measurements to get it done because it matters to them, not because I told them to."

Don't Underestimate the Kids

As part of a summer internship Mytko was developing curriculum for engineering design. At some point, she decided she was "over-designing" it. "I was saying, 'OK, everybody is going to make a pencil cup, and I want everybody to think [about] what kind of pencil cup they want.'" That approach would make it easy for the teacher, she noted, because the students wouldn't "feel paralyzed by choice." But the result, she realized, would be "a bunch of pencil cups that were 3D-printed."

She has learned to replace control with setting boundaries. Now she tells her students, "Let's talk about something purposeful in your life that you'd like to design." That approach is "scary for the kids. They're not used to being asked what they want. So it's messier in the beginning for sure. But the outcome is much more valuable. I have no problems engaging [my students] in their projects. They've dreamed it up, they're invested in it, and they want it to succeed."

The option is still there to print a pencil cup, she added, "but I don't want to limit the kids who have that vision."

Visit Christine Mytko's classroom blog, "Tales of a 3D Printer," at talesofa3dprinter.blogspot.com.