Survey: Teacher Quality, Not Testing, the Best Way to Improve Education

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 08/26/15

A major national education poll depicts a public still disgruntled with efforts to standardize what students should know about reading, writing and math across state borders. The survey found that 54 percent of Americans opposed having teachers in their communities use Common Core state standards to guide what they teach. Only 24 percent favored it. The remainder didn't know what to think.

If the overall findings about the Common Core sound definitive, they may not be. After all, last year, the same poll found that an even higher 60 percent of people opposed the standards, many because it would "limit the flexibility that teachers have to teach what they think is best."

The results come out of the latest education survey conducted by PDK, a global association of education professionals, and Gallup. The poll, financed by the Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, has been conducted for nearly 50 years to explore the opinions of the American public regarding K-12 education issues.

Before 2015, the poll had queried 1,000 people 18 years and older via telephone. This year, the pollsters added a Web component and surveyed more than 3,000 Americans 18 and older who had Internet access. That expansion enabled PDK and Gallup to report on the differences and similarities among black, Hispanic and white respondents.

One of the findings was that black people were the only group that approved of the use of Common Core (41 percent) more than they opposed it (35 percent) As one mother, Myya Robinson, a Mississippian profiled in the survey results, explained, "When I think of the Common Core, I think of it as raising the bar and leveling the playing field. Who wouldn't want high expectations for all of our children?"

Across the board, 64 percent of respondents agreed that there's too much emphasis on standardized testing in public schools. Self-declared Democrats had the highest rate of opposition to testing at 71 percent; black people had the least opposition at 57 percent.

It was a different matter, however, when people were asked whether parents should be allowed to excuse their children from being tested. Among the national total, 41 percent said parents should be able to opt out; 44 percent said they shouldn't. Black respondents were the furthest from national sentiment: 28 percent said parents should be able to opt out, while 57 percent said they shouldn't. In fact only 21 percent said they would excuse their own children; 75 percent wouldn't.

Among Democrats — the group that with the highest rate of opposition to standardized testing — only 33 percent said parents should have the right to excuse their kids; 50 percent said they shouldn't. When asked whether they'd excuse their own child from taking a standard assessment, 26 percent of Democrats said no and 63 percent said yes.

The Data Quality Campaign, which advocates for the use of education data to improve student learning outcomes, believes the "backlash" against student testing has come about because there has been too little value from it for teachers or parents. "Evidence suggests this is changing, but tests need to give parents more than a number that lacks context or meaning," said DQC’s vice president of policy and advocacy Paige Kowalski in a statement. Calling the tests "just one piece of the data puzzle," Kowalksi suggested that "to help create a full picture of their child's learning, parents also need data beyond test scores, like examples of student work and written observations by the teacher."

That ranking lines up with survey results. To understand a student's academic process, respondents placed test scores at the bottom of the list (16 percent), beneath seeing examples of student work (38 percent), having teachers write observations about the student (26 percent) and having teachers give grades (21 percent).

The results of standardized testing also didn't rank high as a way to measure the effectiveness of public schools in the community; only 14 percent of respondents designated that as "very important." Many more said better gauges were the engagement level of students in their classwork, how students felt about their future, and high school graduation rates (78, 77 and 69 percent, respectively).

College and career didn't resonate among Americans as good measures of school effectiveness; only 38 percent of respondents said that the share of high schoolers who went onto college was a good measure; and only 27 percent said the same about high schoolers getting jobs "immediately" after graduation.

For the most part, Americans don't think much of standardized testing as a way to compare results from one school, district or state to another. Those aspects of standardization were considered "very important" by only 18 percent of all respondents and had only slightly more importance (24 percent) when considering how students compared to their peers in other countries.

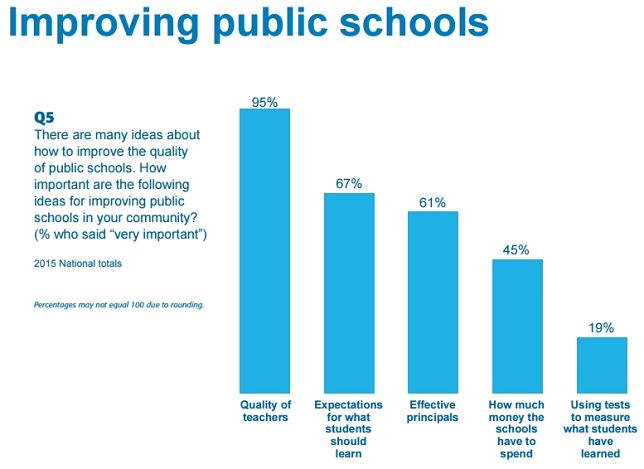

Across the board, Americans believe that teachers offer the best hope for improving the quality of schools. A solid 97 percent of public school parents ranked teachers number one in that regard. The second most important ingredient for improving schools was the effectiveness of the principal (chosen by 67 percent). Close on its heels was the idea of setting expectations for what students should learn (specified by 66 percent). Money is very important to just under half (49 percent) of parents.

Using test results to improve the quality of schools was deemed most important by only 19 percent of respondents. Yet DQC's Kowalksi noted that "good testing" can also give teachers information for adjusting their instruction. "Failing to ensure this key information is in the hands of educators and families means we're not seeing the real value of testing," she added.

The jury is out regarding the level of importance student achievement should be given in how teachers are evaluated. In this year's polling, 43 percent favored tying teachers’ evaluation to students’ achievement (up from 2014's 38 percent), while 55 percent opposed it (down from 2014's 61 percent). Only 37 percent of public school parents were in favor of evaluating teachers based on their students’ achievement.

Lisa Litvin is one of them. This New York mother freely acknowledged in the report that she doesn't like the Common Core; but she's even more against testing tied to the state standards — and that included tying teacher evaluations to those results. "When we heard about grading teachers on the test, it was obvious to us what would happen: Teachers would spend disproportionate time on tested subjects, more time on test preparation, and the curriculum would be narrowed," she said. "They’re not bringing home Wall Street money; they’re just trying to do right by our kids. We have to stop hammering them so much."

The overall results, noted PDK CEO Joshua Starr, suggest that while Americans find testing "necessary," we also as a whole don't believe that tests should be the "end-all and be-all of a public education." What needs to come next is a dissection of their beliefs: Does their antipathy toward testing concern just state standardized tests, or do they also object to national tests such as Advanced Placement, SAT or ACT? What is the role of teacher-created tests? If test scores are not the right evaluation tool, then how do Americans want educators to measure each child's progress?

The results of the 2015 PDK/Gallup poll as well as many other resources related to the survey are available online here.

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.