AV & Presentation

Using Images To Keep Your Class Focused

According to our expert, smart deployment of pictures and videos in class engages students by tapping into the brain's "delight in making connections."

Lynell Burmark is the author of They Snooze, You Lose: The Educator's Guide to Successful Presentations, as well as an award-winning teacher

and highly applauded presenter. Here, she offers tips to help teachers keep students focused during class time.

THE Journal: What do classroom teachers do that's most likely to lose them the attention of their students?

Lynell Burmark: Probably failing to "change it up." No one can sit-and-get for more than 10 minutes without at least 2

minutes of doing something else. No matter how fascinating the talking head, the clock is ticking … Of course, the challenge is exacerbated by

the increasing percentage of students with ADD or what my colleague Rushton Hurley calls ADOSS (Attention Deficit — Oh, Something Shiny!).

THE Journal: What are some techniques you recommend to achieve the 10 and 2 pacing you mentioned?

Burmark: Well, I don't exactly set an alarm at the 10-minute mark, although I may try that in my next presentation, just to

make the point. But I do go through my draft presentation to make sure that video clips, activities and other forms of audience participation

are well distributed throughout the presentation.

THE Journal: Do you find video more engaging than still images?

Burmark: If you are talking about viewing video and images, they both have their place. Video has the advantage that music,

dialog and engaging story lines are often already part of the clip. Videos can also be great for step-by-step instructions. I've noticed my

11-year-old niece Taylor no longer asks adults how to do things. She goes straight to YouTube.

But images offer more options for creative interpretation. I like to say that video gives you answers, whereas images ask you questions.

THE Journal: Can you give us a couple of practical, replicable ideas for engaging students with still images?

Burmark: You are welcome to help yourself to hundreds of ideas in the articles on my Web site educatebetter.org. For now,

let me just share an audience favorite from the presentation I put together for the March 2015 National Art Education Association conference in

New Orleans.

I have been inspired for decades by Bob Marzano's research on the power of identifying similarities and differences. In my teaching, I've

always found pairing and comparing items to be like a two-for-one sale: Students learn both items faster and remember them longer! So I came up

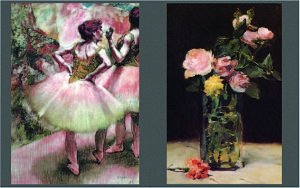

with the idea of making a "BrainTrain" of images where you continue to add an image to compare to the last one before it. For the art

educators, my PowerPoint slideshow started with Degas's Dancers Wearing Pink and Green, then added Manet's Roses in a Glass Vase. The audience

divided into groups of three and discussed the similarities between these first two paintings.

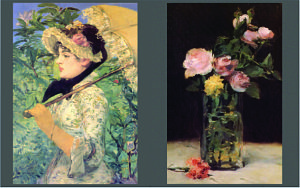

I then replaced the first image, the Dancers, with a woman holding a parasol, Manet's Spring.

And finally, I replaced Roses with John Singer Sargent's A Morning Walk.

With a slideshow, this becomes sort of a ping-pong activity. (In fact, I had initially called it "Ping-Pong Pictures.") If, instead, you

were to print the images out, they could become the visual BrainTrain of connections, working their way like a never-ending train around the

classroom, until the wall space was covered or it was time to move onto another topic — whichever came first. You can create a BrainTrain

slideshow on the iPad or iPhone by using a free app called Frametastic that lets you size images behind frames.

Participants in the lecture I mentioned above noticed things like "same color palette," "same artist" or "same subject matter." But given

more time and more sophisticated observers, more subtle comparisons emerge. For example, one viewer was struck by the hand positions of the

women holding parasols and compared that to how you would hold the bow while playing the cello. (Yes, we enrich the images with our own life's

experiences!)

This works equally well with images that are similar and images that — at first glance — have nothing in common. The brain delights in

making connections, and it's the connections between the images that become the glue to stick both images together for the activity and in the

students' long-term memory.

Of course, in the classroom, this becomes even more engaging because it's small groups of students (rather than the teacher) who present the

next image. They can ask the rest of the class how/why it fits and then give their own reasoning as well.

THE Journal: In this thinking-train activity, the students alternate between viewing images produced by others and adding

images themselves. Is that a significant shift?

Burmark: Absolutely. But it's really a third step to that shift that I believe can and will transform education.

Traditionally, students consume the teacher's teaching plus whatever research they conduct as part of the topic or class. Then they produce

something (a paper, report, presentation or form of media). My colleague Warren Dale refers to this most broadly as their "proof of learning."

It gets interesting in my mind when the proof of learning for one student is shared in ways that it becomes the path to learning for the

rest of the class. This is most efficiently accomplished when the proof of learning has a strong visual dimension and becomes what I call

"Visual Proof of Learning." In the BrainTrain activity, that third step creates a cycle of consuming/learning, producing/teaching,

consuming/learning that continues for as long as it makes sense for the topic in question.

I have to chuckle when I hear education pundits proclaim that we have shifted from teaching to learning — as if the one precluded the other!

What is happening is that engaged students are learning and teaching their peers in ways that teachers never could. Lines blur between teacher

and student as everyone consumes and produces at various points along the path to learning.

THE Journal: In closing, could you share with us your top three tips to help teachers keep students engaged?

Burmark: Just three? These may not be the "top" three, but they are a good place to start:

1) Put students in groups. There's a Vietnamese proverb that says: "Respect your teachers; learn from your friends." In most

cases, students do not come to school to listen to their teachers. Put their social energy to work in teams for creative activities and

project-based learning.

2) "Words can never recall an image we haven't already seen." (Yes, I made that up, but I challenge anyone to refute it.)

Use those LCD projectors; design activities that build from images that students select or montages and videos that they create.

3) Deploy and encourage humor. I don't advocate gratuitous humor — "Okay, class, let's take a break while I read you a

joke" — but rather humorous juxtaposition to make a point, funny images that spark rich language and story lines and hilarious observations

from students that add to the breadth and depth of understanding of the topics being discussed. In my opinion, the most valuable use of class

time is to let laughter erupt from students' comments that connect our ideas to their thinking, to their world and — in those moments of magic

— to their hearts.