Data Driven Math Instruction for the Common Core

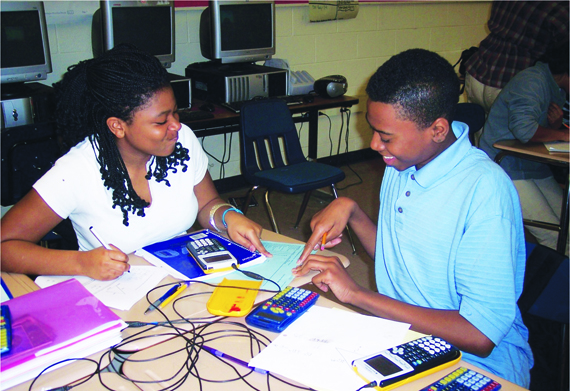

Students at Eastway Middle School in Charlotte, NC, use graphing calculators to send data to their teacher as part of a Texas Instruments algebra-readiness program known as MathForward.

The impending switch to Common Core State Standards will require a transformation of teaching and learning in K-12 classrooms across the United States. Many current teaching practices simply will not provide students with the necessary skills to be productive 21st century citizens, and most educators recognize that fact. However, changing a teacher's practice and a school's culture are daunting tasks.

At Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (NC), where I work, a number of students and teachers are bringing in sweeping change as they move toward full implementation of the Common Core's Standards for Mathematical Practice. They are reimagining the way math teachers are trained and students are taught, using an approach that makes use of technology and focuses on professional development.

Specifically, more than two years ago the district began employing a Texas Instruments initiative called MathForward that combines the use of technologies like graphing calculators and a navigator system (which allows teachers to collect instant feedback from students), a heavy focus on professional development, and differentiated learning. The program can be used in conjunction with any textbook, because it's not a curriculum--it's a way to change the teacher's pedagogy and work in the classroom. Today, the district's Title I middle schools (150 classrooms) and high school Algebra 1 classes (100 classrooms) are enrolled in the program.

As part of its overall Common Core implementation strategy, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg district's principal focus now is on the core's W-1 standards, which, while not math-specific, focus on evidence-supported argumentative writing, a skill that applies to all content standards. W-1 is about using data to form opinions and to back up those opinions. A central part of the MathForward program incorporates using math-based data to support a student's hypotheses.

Teaching Teachers First

The program consists of multiple parts, but it all starts with the teachers, who begin with five days of face-to-face training on using the technology and research-based pedagogy for math instruction. Then, four days each month a program coach observes teachers' classrooms and works with them to create lessons that take advantage of the data teachers collected from students (i.e., test scores and homework answers). Then, four to five times a year, all participating teachers are pulled out to learn more content and work as a professional learning community.

The program is in use every day in the classroom. When students come in, teachers ask randomly selected homework questions, and students answer them using buttons on their graphing calculators. The questions could be multiple choice, fill in the blank, or even open response. The data is then transmitted to the teacher's navigator system, where teachers can display the answers for the entire class without identifying which student offered which response, and also privately identify which student gave which response. . Teachers then can say, for instance, "We need to go over No. 7, a lot of you missed that." The great thing is that it gives the teacher immediate buy-in. They see instantly that this is something that can make their lives easier.

The students have taken to it too. If they have 15 homework problems and everyone in the class got 14 of them right, they know they won't have to spend 30 minutes in class going over it. The teachers can focus instruction on the areas in which the students need the most help.

In these MathForward classes, students also spend about 20 minutes of each class solving what we call "real-world problems." Texas Instruments has a team that scours the news and develops topical situations that students can think critically about.

For instance, last year, when oil was spilling into the Gulf of Mexico, students spent about eight weeks looking at data coming in from the region and solving problems based on it. They used Google Earth, their math skills, and various technologies to digest the just-in-time data the experts were generating. Kids then learned to ask questions to try and solve these problems. Each day, after they spent some time on the Gulf oil spill problem, they moved on to a regular math lesson, and then returned to their real-world problem with teachers asking if what they just learned would help them solve--or think differently--about the problem.

Obviously, we did not expect students to solve many of the complex, theoretical questions that were posed--the experts do that--but students learned that you need to use math to solve these types of problems and, in doing so, they used every one of the eight Standards for Mathematical Practice in the Common Core, from reasoning abstractly to attending to precision.

In addition to making sure students employed the standards, we also felt it was important to make them aware of what they were doing. Each math classroom has posters on the walls demonstrating the eight math-related standards with an aligned graphic. Students are expected to write a "ticket out the door" each day explaining what they learned in class, and which mathematical practice they employed. The practice also reinforces our focus on W-1 argumentation--using data to form an opinion and then being able to back up that opinion--since what we are really asking kids to do is to take information, analyze it, and communicate about it.

Differentiating Data

For the teachers, the professional development part of the program is the real hook, because the ultimate goal is to change their practice so they can be better teachers for all kids. But they couldn't do it without the technology to take care of a lot of the grading and differentiating.

In MathForward classrooms, teachers typically collect 15 to 20 points of data about students every day. Instead of teachers having to spend time grading these problems, they now spend time reflecting on who is struggling with what and how they can best meet their needs. The technology, coupled with the face-to-face coaching, is enabling them to differentiate. The teacher, who in the past could only provide two to three different assignments to differentiate, can now provide as many as 30 different assignments.

From the first implementation of MathForward more than two years ago, we have seen significant improvements. In particular, 23 eighth-grade classrooms produced two years' worth of growth in student achievement in one school year, and several schools are moving student mastery on state tests from 40 percent to nearly 90 percent. Special education and limited English-proficiency students have shown four to five years of growth in these classes because of the engaging technology and teachers' instructional practices.

In the schools that have been using MathForward for more than two years, the culture of math has been transformed to one where all students know they can master difficult math concepts. Teacher retention in high poverty schools has always been low, but the success teachers experience with the support and technology provided by MathForward has improved the retention rate in our Title I middle school math departments to more than 90 percent. The rigor of the Common Core standards requires students to begin using graphing calculators in the sixth grade and, with MathForward, our teachers feel empowered to do that successfully.

Creating a Common Core Toolkit

The overall move to the Common Core State Standards presented Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (NC) with a number of challenges. Among them was the dearth of collected resources freely available that teachers could turn to in making sense of the new standards.

To counter this deficiency and help teachers and administrators prepare for their new roles, district leaders created a comprehensive internal resource that compiles webinars, video clips, and samples of student work, all revolving around the new concepts and standards. Called the Common Core toolkit, the resource serves as a compendium of everything schools need to begin preparing themselves for the shift. For teachers, multimedia is paired with recommended websites, like insidemathematics.org, and whole lesson plans. For principals, there are video demonstrations of administrators observing lessons and discussing them with staff.

"It's the district place where we put high-quality resources," explains Cindy Moss, the district's director of PreK-12 STEM education. "We've already juried what's out there, so you can trust that it's high quality."

Ultimately, teachers will be able to take as much as 80 percent of their lesson plans directly from the toolkit, enabling them to train their focus on changing their practice, not creating lessons.

"We have almost 10,000 teachers," Moss says. "You can have a really great teacher that's not great at writing lessons, so we have always provided alignment guides and pacing guides. We provide lessons that focus on the appropriate content to the appropriate level of rigor."To develop the toolkit, the district created a Common Core steering team with curriculum and assessment specialists, special education experts, ELL teachers, and other stakeholders who will be affected by the switch, including parents, who were represented by leaders of the district's Parent University, which offers free skill-building courses. The team then wrote grade-level-specific lessons in subjects like language arts, math, and science. Afterward, stakeholders were allowed to examine it with their specific populations in mind.

As Moss explains, "The ELL rep might take it and make some modifications that might be needed for a kid who is an English language learner, the special ed might make some recommendations for some modifications a kid with a certain IEP, and the Parent University representative would look at it and say, 'Here's a paragraph we need to send home to parents when students are learning these units.'"

The best part is that Charlotte-Mecklenburg is sharing its toolkit with other districts. Currently, Moss says, the toolkit is not accessible online; however, she hopes that will change next year. For now, interested districts can gain access to the toolkit upon request. For more information, contact Cindy Moss using this form. --Stephen Noonoo

|

About the Author

Cindy H. Moss is director of PreK-12 STEM education at Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina.