Making Search Engines Work for Education Resources

The Learning Resource Metadata Initiative has a complicated name but a simple purpose: to make web searches more useful for students and teachers.

- By John K. Waters

- 02/12/13

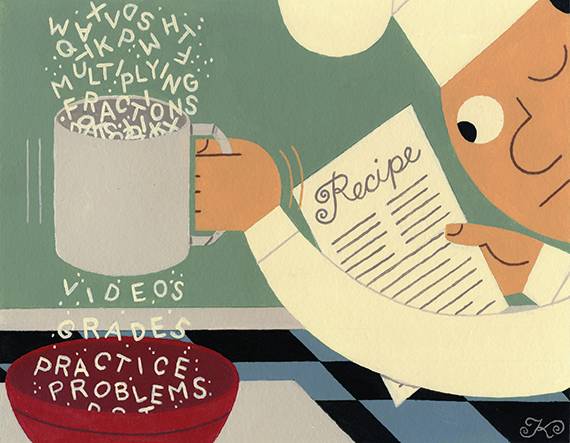

Try this for information overload: Open your favorite browser, and in the search box type "multiplying fractions." In about a quarter of a second, you'll find yourself buried in more than 4 million results. Four million. Even with web page-rating schemes like Google's PageRank pushing content deemed more relevant to the top of the pile, that's one massive, needle-obscuring haystack of information.

For everyone involved in K-12 education, "It's overwhelming and frustrating and causes a negative online experience," says Dave Gladney, project manager for the Association of Educational Publishers (AEP). "Students and teachers struggle with it, and the creators of educational content get lost in it. What's needed is a commonly agreed-upon vocabulary for describing content for education search."

Gladney says that finding "a common metadata specification for marking up online content that is educational in nature" is the aim of the project he is managing, the Learning Resource Metadata Initiative (LRMI). The initiative is co-led by the AEP, a nonprofit organization of professional educational publishers, and Creative Commons, a nonprofit that provides alternative "copyleft" licenses for creative works that allow others to build on them legally.

The collaboration is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Gladney says that the AEP was invited by the Gates Foundation to lead the LRMI project, but Creative Commons is overseeing much of the technical working group activity as well as providing a "huge conduit" to the open educational resources community.

The LRMI, which was announced in June 2011, has the stated goal of developing a metadata framework for describing educational content and products on the web that will make online learning resources more "discoverable" so that students and teachers can find relevant resources more easily.

The Wider Problem of Narrowing Data

The problem these organizations are trying to solve is not a new one, of course, and certainly not limited to education-related searches. But the announcement last summer that the leading search engine providers--Google, Microsoft (Bing), and Yahoo--would be working together on a solution for their general web searches threw a spotlight on the issue. Gladney says that seeing the giants of search working together provided some of the impetus to develop LRMI, which he sees an extension of that project--but with a tight focus on education.

"Even though they're fierce competitors, they decided to collaborate on a set of tagging standards for web content in general," Gladney says. "I think all three of them signing on and agreeing to work together was a motivator for people to take notice of this problem and to start doing something."

The big three search engine providers were recently joined on the project by a Russian search company, Yandex. Their initiative, dubbed Schema.org (in computer science a "schema" is a kind of database blueprint), is developing a common vocabulary for structured data markup on web pages. Structured data are organized and identifiable bits of information, typically defined in rows and columns. The schemas the group is developing are data types associated with sets of properties, starting with very basic designations such as "thing," "place," and "person"; and expanding into subtypes such as "book," "DanceGroup," and "city." Webmasters will use HTML tags based on these schemas to enhance the content of their web pages for more precise search results. HTML is the hypertext markup language used to display web pages in a browser.

The key concept here is "metadata," which might be defined as data about data. Metadata--or more precisely, descriptive metadata--describe both the content and context of data files. They're the who, what, when, where, how, and even why associated with a particular data set. The addition of metadata to web pages helps the search engines to better "understand" the content of those pages and provide richer search results.

Searching for Potato Salad

The LRMI spec describes a focused range of data properties, such as "intended user role" (say, "student" or "teacher"), "typical age range" (say, "7-9"), and "learning resource type" (say, "presentation" or "handout"). It does not bother with properties that have been "adequately expressed" in Schema.org, such as "name," "author," and "media type."

To illustrate how this tagging strategy would help students and teachers engage in more productively focused internet searches, Gladney (and just about everybody T.H.E. Journal talked to about this project) uses the example of searching for the keywords "potato salad." If you type those words into a Google search box and click "Enter," the search engine will return a list of more than 43 million potato-salad-related web pages. This sea of data will include a ton of recipes, of course, but also the Wikipedia entry for potato salad as well as many non-recipe articles on the subject.

To filter the search so that you see only recipes, click on "More" in the row of options under the search box, and then "Recipes" in the drop-down menu. Google will return a list of 7,700,000 pages of recipes. Better, but if you want to refine your search even more, click "Search Tools" to enable three more options: "Ingredients," "Cook Time," and "Calories." Using "Ingredients," you can search for potato salad recipes with or without mayo, mustard, paprika, dill--even potatoes.

"The idea is to provide students and teachers with the ability to refine their searches in this way," Gladney says. "We ultimately envision the LRMI enabling search filters in educational resources for things like subject area, grade level, alignment to standards like Common Core, and media type."

Getting Publishers on Board

The official release of LRMI's first framework is fast approaching. The project completed Phase I of the project in March 2012, after which a draft spec was submitted to the World Wide Web Consortium public mailing list for web vocabularies. This was the first step toward being adopted by Schema.org as the standard online metadata schema for learning resources. The LRMI is already the metadata framework required for all resources that will be in the the Shared Learning Collaborative, an industry alliance focused on personalized learning. The list of metadata tags in the near-final specification is posted on the LRMI website.

Phase II of the LRMI, currently under way, is a proof-of-concept (POC) project involving early adopters of the spec. This is an important step, Gladney says, because the success of this initiative depends not only on a shared markup vocabulary, but on the participation of the publishers. "Once the spec is finalized and published, it's really up to the educational publishing community to tag their own content," he says.

One early adopter is Roger Rosen, president of Rosen Publishing, which provides supplemental educational books and materials to libraries and K-12 schools. "I and my team jumped on a chance to participate," he says. "In fact, we've submitted more than a thousand books for data mapping so far." Rosen himself also serves on the AEP board.

"This is all about discoverability," Rosen continues, "Teachers and students need to know what is available, and the standard Google search is woefully inadequate, especially in terms of relevant educational content. There hasn't been the sort of detailed tagging available that would allow, for example, a fourth-grader reading at a second-grade level researching the history of California to find content that is specifically appropriate to them. There hasn't been a way for them to find, quickly and easily, material that is spot-on for their needs."

Lee Wilson, CEO of PCI Education, a publisher of digital and print materials for special education and struggling learners, agrees. "Search is one of the great barriers to online content," he says. Wilson, who is the current president of the AEP board, participated in the project's Technical Working Group, and his company was also part of the POC project. He got involved because, "There is so much stuff out there that being able to filter it quickly and on the fly--in ways that make sense--has been tough, particularly for classroom teachers."

In October, the AEP kicked off a monthlong campaign to raise awareness of "the negative effects of information overload on educators' and students' online search." The Easy Access and Search for Education (EASE) campaign invited K-12 district-level administrators, principals, curriculum leaders, librarians, and classroom teachers to share their opinions and suggestions about online search.

"Out of this process--the POC and the EASE campaign--we expect to develop some best practices that will help us to provide publishers with useful guidelines based on real-world experience," Gladney says.

Gladney is among those also promoting the LRMI specification as a framework for learning management system (LMS) developers. "We hope that it will be applied beyond internet search," he says. "We believe it has application in things like LMSs and platforms that are being developed for personalized learning."

Wilson sees LRMI differently, saying, "Some people want this specification to be something more than it is. But one of the things I like best about this project, and one of the reasons I think it's going to be so effective, is how tightly focused it is. This is really just about discoverability of highly relevant materials. I've identified either a class or kid with a very specific need; what resources are out there to help me help him? That's what's needed, and that's where we should be."

About the Author

John K. Waters is a freelance journalist and author based in Mountain View, CA.