Mobile Learning | Feature

These Gorgeous iPad Notes Could Lead to the Paperless Classroom

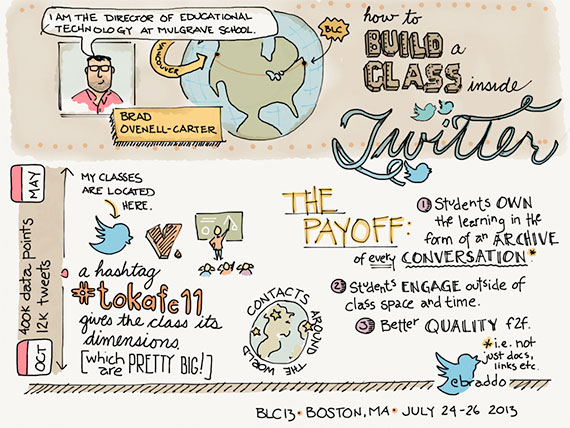

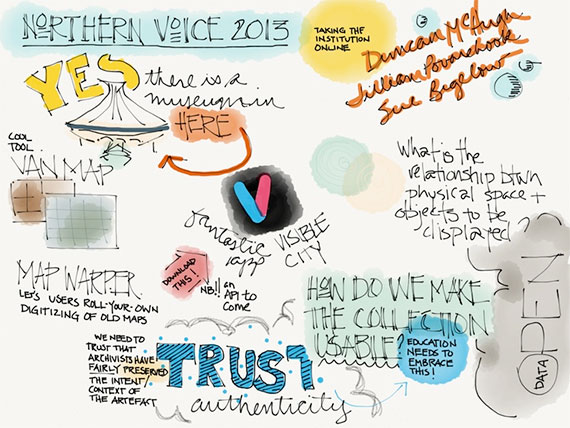

A sketch-note page by Brad Ovenell-Carter's made with the iPad app Paper, via Pinterest |

Vancouver teacher Brad Ovenell-Carter has been doodling notes in Moleskine notebooks at conferences for a while, causing heads to turn. People used to ask him for copies and he would snap a photo and send it to them.

When the iPad came along, Ovenell-Carter migrated his "sketch-notes" to his tablet, using a stylus to draw into an App called Paper (he preferred its simplicity to higher-end tools for graphic designers). That’s when he became an exemplar for the growing sub-culture of paperless learners, doodlers, iPad-only learners, live-scribers or — his personal favorite — "sketch-noters." Their craft raises new questions about the future of learning and even communication.

In March of 2012, Ovenell-Carter was at an education conference doodling on his iPad and someone next to him suggested he Tweet out the notes. "So I did," he said. "I decided I would tweet them out and if they make sense to you, great. If they don’t, no sweat. They are just my notes." His Pinterest page and Twitter feed have ramped up with enthusiastic followers.

Sketch-noters have their own club called Sketchnote Army, led by Milwaukee-based designer Mike Rohde. He’s been championing sketch-notes since 2003, authoring The Sketchnote Handbook. His Sketchnote Army site profiles sketches from the growing community that includes more than 1,300 Twitter followers. Another practitioner, Rachel Smith, gave a popular TEDx talk about "Drawing in Class" that explored the potential for taking visual notes, a hobby-turned-profession for her, which she calls "graphic recording." She argues that visual note taking only requires listening for relevant points to jot down and doesn’t require immense artistic ability.

|

How It Works

Many practitioners of sketch-noting use a stylus pen to draw on the iPad and use a drawing app such as Paper combined with apps like Evernote or Google Drive to save and manage notes in the cloud. Some snap their own photos of blackboards or PowerPoint slides, integrating images into their visual notes. Others grab photos from the web, cropping and dropping them into their notes and jotting maps, arrows, and words to connect and illustrate the ideas. Using this technique, Greg Kulowiec, a consultant on iPads and education for schools with EdTechTeacher, said he ends up with fewer pages of notes but that they're more impactful and relevant.

"It’s the idea of moving away from linear, text-based notes with a traditional outline format: bullets with idea after idea in list form," Kulowiec said. "If you can move to non-linear fashion with images, you can bring in and crop pictures to capture your thought process."

By day, Ovenell-Carter is director of education technology at the Mulgrave School in Vancouver, where he also teaches literature and philosophy. He represents a bleeding-edge group of ed-tech users who stretch the sketch capacity of the iPad (or other devices) to the hilt. Such uses of the iPad are showing up in the advertising industry, graphic design scene, and art world. But Ovenell-Carter says sketch-noting has a logical place in education and, agreeing with Rachel Smith, said the practice is not just for the art-inclined.

"My notes, I still say, are for me. It’s not an art project. We have to get over that idea (of sketch-notes as art). It’s a huge limitation," he said. "Human beings are visual communicators. We communicate first with pictures and then words."

Ovenell-Carter has no formal training as an artist, though he has an interest in design aesthetics and Avant-Garde art. Sketch-noting was just "one of those things that I thought I’d try to get better at." It became a hobby like playing a musical instrument; a hobby for his own sake rather than for performance.

Sketch-noting "inverts the traditional note-taking process," he said. "You are not trying to capture everything. You are looking for high-level ideas. I never write any piece of trivial knowledge down that I can look up later." Rather, he only writes (or doodles) ideas that resonate with him. In this way, he finds the practice much more useful than text-based notes. "When I come away from a conference, I have a better idea of what the speaker was trying to say. I’m not caught up in processing details."

Doodling in Class

At the 780-student school where Ovenell-Carter works, he has started experimenting with sketch-noting in his Theory of Knowledge class in the International Baccalaureate (IB) program. He divides up tasks in his classes, deputizing one student as a note-taker and another as a community builder, for example. Some students prefer to draw on a white board and the class takes photos of the notes and adds it to the class files. Students also participate in a live blog and tweet about everything said in class. An archive of these discussions are kept in a Google spreadsheet and the sketch-notes in Storify. "Now, we have a really nice record of our conversations."

These days, Ovenell-Carter is experimenting with concepts like having students author their own textbooks. He wonders, along with Danish Prof. L.O. Sauerberg, whether Guttenberg’s invention of the printing press merely made text a dominant means of communication for centuries. Now, perhaps, knowledge and learning is moving back to other means of communication.

Ovenell-Carter collects books but, at the same time, has gone essentially paperless, only printing documents when he absolutely must. You might see him at conferences this year from Stockholm to SXSW in Austin in March. "I see a real appetite with this stuff."

About the Author

Paul Glader is a Berlin-based writer and journalist whose work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Associated Press, and the Wall Street Journal, where he spent nearly a decade as a reporter.