New Report Looks to Data for Helping America's 1.3 Million Homeless Students

The number of homeless students in the United States has doubled since the 2006–2007 school year. New federal law that goes into effect with the new school year is designed to make it easier for those students to complete their education.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 06/20/16

In Colorado, whereas 77 percent of all students graduated from high school in 2014, 53 percent of homeless students earned their diplomas. The disparity is even greater in Washington State, where 77 percent of all students graduated from high school, but only 46 percent of homeless students did so. Two-thirds (63 percent) of Seattle homeless youth had six or more absences in a 2013-2014 survey, compared to 38 percent of low-income students. The homeless were also more likely to be suspended or expelled, according to the survey, and to drop out of school altogether.

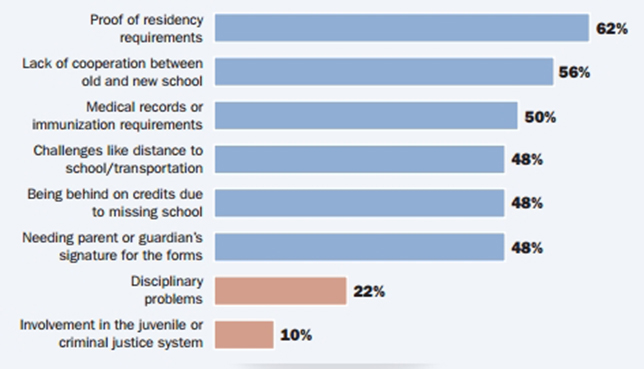

On top of that, all over the country, changing schools or enrolling in schools becomes a major hurdle for homeless students because they may not have medical records or immunizations, be behind on credits, lack a parent or guardian who can sign forms for them and just struggle with the daily chore of getting to school in the first place.

However, as a new report from the National Center for Homeless Education suggested, data could provide the impetus needed for school districts, states and the federal government to help this growing population of students do better in school.

As "Hidden in Plain Sight: Homeless Students in America's Public Schools" reported, the number of homeless students in the 2013-2014 school year reached about 1.3 million, more than twice the count of the 2006-2007 school year. Homeless students are children and youth who "lack a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence." They could be sharing the housing of others owing to their own loss of housing or economic hardship; they could be living in motels or hotels, trailer parks or campgrounds; they could be residing in shelters; they could be living in cars, parks, abandoned buildings, bus or train stations or similar places; or they could be continually moving from one of these options to another.

Homeless youth were asked to specify what types of challenges they faced in changing schools or enrolling in a new school while they were homeless or in a "very unstable housing" situation. Source: "Hidden in Plain Sight: Homeless Students in America's Public Schools."

Policy Changes for Schools

The passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) last year boosted the strength of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, as the report's authors stated, by pushing schools to identify their homeless students and to work more closely with them in providing for their education. That will require more training of a wider portion of school staff to help them identify the signs of homelessness and will pressure schools to gather residency information from students and families at multiple times during the year, not just at the beginning of the school year.

Schools will be expected to better make students and families aware of their McKinney-Vento rights and the services and supports available to them inside and outside of school.

ESSA also wants to see schools address the problems associated with keeping homeless students in class by being more flexible with policies about attendance and homework deadlines, helping them work around legal issues that require parental consent or participate in school activities and becoming more creative in how they deal with delays in the transfer of transcripts and test scores that previously could have kept these students out of school.

Those policy changes officially go into effect with the new school year; but the report acknowledged that making change on the ground will take longer because schools will need to learn about their new responsibilities and how to more accurately assess the size of their homeless student populations.

Funding Homeless Student Supports

The extra obligations imposed in ESSA were accompanied by a bit more money. ESSA increased funding for McKinney-Vento to $85 million per year for fiscal year 2017 through 2020. This represents a 21 percent bump from the current level of $70 million. Under the new law, McKinney-Vento "subgrants" may now be used for emergency assistance in order to help homeless students "attend and participate fully in school."

At the same time districts schools receiving Title 1A funds are expected to set aside a "portion" of their funds to support the education of homeless students. And states must include information about the graduation rates and academic progress specifically of their homeless student populations in their federal reporting.

The use of data will play a crucial role in helping these students, the authors insisted.

For example, the report noted, communities already track data across a number of slices — social, economic and educational — in order to help "vulnerable youth." Now they need to better pinpoint youth who are homeless and use it "to drive progress."

Similarly, states and the federal government should consider setting a national high school graduation rate for homeless students, similar to what is already in place of other subgroups, such as English Language Learners. The new ESSA reporting stipulations, the report suggested, could be used to monitor progress and "keep schools, districts and states accountable."

The report recommended a progressive increase "towards" a 90 percent graduation rate. If that sounds overly ambitious, consider the HOST program in Mason County, WA. That community effort, which is supported by several regional organizations from the Rotary Club to the Gates Foundation, supplies community-based host homes and transitional housing to support homeless students. Participants also receive financial help, life skills development and educational support. HOST has been in place since 2013, and "eligible participants" have a 98 percent graduation rate; 85 percent have gone to college or become employed within six months.

Finally, the authors suggested making homeless student data "smarter and more accessible" so that agencies could share it more easily. One example offered: allowing homeless student school liaisons to insert student data into the Homeless Management Information System, which is maintained by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Opening Doors, a federal plan to prevent and end homelessness, was released in 2010 by the Interagency Council on Homelessness. That strategy was revised in 2012 specifically to address how to improve the education of homeless students. Along with building capacity for better delivering services to those in need was the recommendation that the federal government do a better job of "improving data quality and collection methods."

That's essential, according to "Hidden in Plain Sight," because the use of more accurate data can help service providers "better target their efforts and resources to identify and serve homeless families and youth and ensure that their experience of homelessness is as brief as possible and does not reoccur."

The report, which was developed by Civic Enterprises and Hart Research Associates, is available on the Civic Enterprises website here.

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.