5 PBL Strategies from the Champs

Creating "gold-standard" project-based learning requires effective training (and more training), staying light on your feet and getting top leader commitment.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 01/08/20

While any teacher will tell you he or she uses projects in the classroom, that's not necessarily the same as "gold standard" project-based learning — at least not as envisioned by PBLWorks, a nonprofit consultancy run by the Buck Institute for Education that advises schools and educators on their PBL capabilities and produces PBL resources.

Gold standard PBL adheres to a model that incorporates seven "essential" project design elements, such as the use of student voice and choice and creation of a "public product."

Each year during its annual conference, the organization highlights schools and districts that are doing exemplary work. Recently, representatives from two "PBL Champions" — Texas-based Burkburnett Independent School District and Colorado-based Billie Martinez Elementary — shared their guidance for implementing high-quality PBL.

Training is at the Essence of PBL

To succeed, PBL can't be "one and done," said Burkburnett ISD CTE Coordinator Casey Hunter. Her district pulled everybody — teachers, principals, assistant principals, staff at central administration, and even Superintendent Tylor Chaplin — in for three days of training. Lack of time wasn't an excuse. The district offered "PBL 101" eight times during the summer of 2017.

That initial training, which used experts from PBLWorks, primed the pump and set people off doing projects, but as Hunter explained, in many cases "they were just doing what we call 'dessert projects' — fun but not really helping students learn the content through the process of inquiry." How do you tell a dessert project from a "main course"? As Hunter noted, "Dessert projects are 'learn-learn-learn, create a diorama.' Whereas PBL is 'learn-apply-learn-apply and then present your knowledge through various means."

When Hunter and her colleague Testing Coordinator, Linda Borchardt, pushed teachers in those early days to consider whether the projects they were having students tackle were helping them learn the content they really needed to learn, often, the complaint they heard back was, "We don't have time, we don't know how to do this, we're struggling..."

So, a year later the pair came back with "Camp PBL," which included national faculty from PBLWorks and district people leading training sessions and giving teachers time to work on their projects. They also ran eight professional development days sprinkled through the year (reduced to six in the current school year), to give teachers even more time to come together as teams and revise and improve their projects.

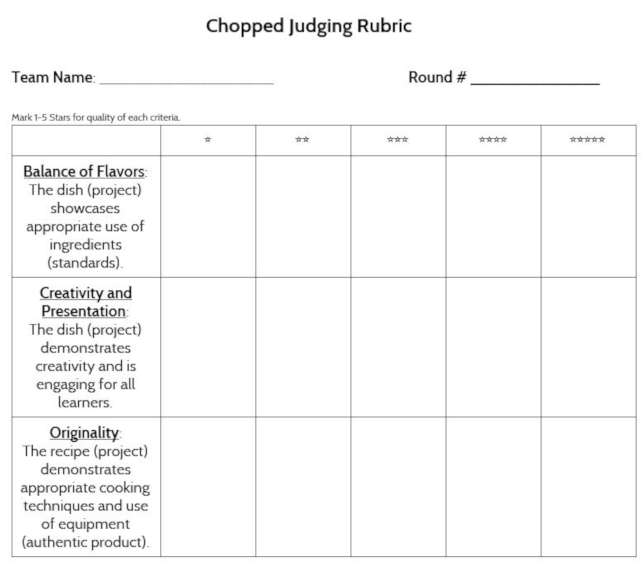

The summer of 2019 introduced "5 Star PBL," which again featured sessions and time for project planning. But it also included a "Chopped" competition, based on the Food Network reality show, where chefs are given a set list of ingredients and must come up with meals that use every one of them. In Burkburnett's case, mixed teams of teachers were given standards from random content areas — PE, music, science — and expected to create "the bones of a project" for a given grade band in 15 minutes. Then they had two minutes to present their projects to a judging panel that included the superintendent and teachers from various campuses, outfitted with an evaluation rubric based on high-quality PBL.

According to Borchardt, the competition "was a lot of fun for teachers. They really, really enjoyed it." But more importantly, they received a lesson in how to create projects outside of their own content areas. Teachers tend to "focus on the content that they teach, and it's hard for them to think about stepping across the hall to the teacher who teaches a different content to get together and create a project," she explained.

And because it was fast-paced, participants could see that they were capable of "thinking rapidly," Borchardt added, and using the rubric for quality against the projects they were coming up with for their own classes.

And the learning has to continue no matter how experienced the educator. Every Wednesday at Martinez, said Principal Monica Draper, the staff breaks into smaller groups and meets for half an hour so teachers from across the school can talk to each other, to share what's working and what's not. The purpose: to get new ideas.

PBL in Action: Zombies Come Back to Life

One elementary English language arts teacher at Burkburnett ISD captures her students' attention around Halloween by talking about zombies. The goal: to teach them how to do research about historical figures. By the end of the project, the students become historical figures themselves and "come to life" in a museum setting. This teacher "gets her kids to reflect and to collaborate with each other, and she gets them to revise their project in the middle so that...students are learning the content, but they're also learning some other skills along the way," said Borchardt.

Teachers Need to Relinquish Their Grip

Letting go is a persistent problem for teachers grappling with PBL. Borchardt shared the story of an elementary music teacher who runs an end-of-year musical performance that all the grades participate in. Until recently, she was the one to write the music or develop the story theme for that event, to which parents were invited. The first year she handed it over to students to produce, including creating the costumes, she couldn't help but be judgmental about the results grade by grade as they were unfolding on the stage — until the end, when the whole audience rose "in a roar of applause." As Borchardt recalled, the teacher told her, "I was so afraid to let go and let the kids be in control of their own play. But now I see that they've learned so much more than they would have had I been the one to write their music or write their play."

At Martinez, the teachers watch what the kids are doing "every day," said Draper, "and tweak PBL opportunities for them based on that. For example, one state-mandated a unit is supposed to cover mixtures and solutions, a subject that's "hard and boring," she said. By working with resources produced by the Literacy Design Collaborative, the teachers tied the lessons to the international water crisis so the students could learn about "how many people in our world don't have access to clean water." The students made a commercial and put that out to all the rest of the kids in the building. Then they also chose an organization they wanted to work with to support getting clean water to people and did a fundraiser. "We sent them close to a thousand bucks. Teachers had not planned to do this fundraiser and send money to this organization That came from the kids and the reading that they were doing about what was going on and the organizations that were helping." That was an opportunity "that the teacher needed to listen for," she explained.

PBL in Action: Studying the Human Body

Grade 5 students at Martinez have studied the human body before. But PBLWorks suggested that they take on the subject by becoming medical students. After learning about the different body system, the culminating project required them to "do their medical boards," marveled Draper. "They were given a patient and symptoms. Based on those, they had to diagnose what the patient had and what the treatment plan would be. Then they had to develop their presentation and present what the illness was or what the diagnosis was. That was so incredible."

Go Big or Don't Bother

A team of nine teachers from Martinez headed to PBLWorks headquarters in Napa, CA for PBL training and then repeated that in summer 2018 for more advanced training. Based on the excitement shown by their students, "we jumped in," said Principal Monica Draper. Next, the school brought in two of PBLWorks' national faculty to work with the entire staff.

Now it's a way of life. Students get 90 minutes every single day — even the first graders — in which they're "attached to project-based learning in some way," Draper said.

"They are engaged every day in these pillars for PBL — collaboration, inquiry, learner agency, creativity and all of those pieces that we know they need to be able to go after any problem," said Draper. "When our students leave Martinez, my goal is that we will have created kids who are curious about their environment, curious about their world and more than able and capable of being handed a problem and knowing where to start, how to research and get feedback and all of those things."

Likewise, PBL isn't a nice-to-have in Burkburnett; it's an expectation. Teachers are required to run at least three projects throughout the school year. The work also adheres to Texas education "readiness" standards, which specify how many days are expected to be spent on specific units. To help them with planning and implementation, each campus in the district has an "innovation specialist," who also helps teachers with technology integration in the classroom, "data pulling" and professional learning community efforts. "But they were initially hired to do PBL and that's a really big role," said Hunter.

PBL in Action: Poetry in the Park

After tackling a set of lessons on poetry, high schoolers create a final product in which they write their own poems and "find, create, [and] transform a personal artifact," said Hunter. Those are transported to the local park, where members of the public are invited to come and read the poems, view the objects and — if the students happen to be around — talk to the poets themselves. Some students have built models of the football field and put their poems there; others have used a tennis shoe or broken glass. Hunter recalled one student who put his poem on a tire. "It was about his grandfather and the work they did during the summer on the grandfather's ranch. After talking to the student, I talked to the teachers and they [told me], 'That kid is so quiet; he never really shares.' But the story through the poem was just really incredible."

Use PBL as a Learning Bridge

Teachers at Martinez pair second language learner students "thoughtfully," said Draper, who marvels at bilingual students' facility in switching from Spanish to English and back again as the work proceeds.

Recently, she was watching a fifth-grade duo researching a project. "They were talking to each other in Spanish, asking each other questions in Spanish. They would read or watch the video, which is all in English, and then they would talk to each other in Spanish again and then write their answers in English." Ten years ago, she observed, the students who mostly spoke Spanish would have been in an English-only class, learning English instead of being engaged in science."

PBL in Action: Reconsidering the "Monuments" Unit

Last year at Martinez the first-grade teachers reworked a unit on monuments ("Let's build a model of the Washington Monument") and decided to work with a local artist to paint a mural in the space as a different kind of monument, this one dedicated to the namesake of the school itself, a parent who was involved at the school in the 1960s. "Her kids are still around, so for part of that project her son and grandkids came over to be interviewed by the first graders so that they could get to know who she was," said Draper. This year the artist has returned to continue that project with the same group of students.

Top Support is Essential

Without buy-in from leadership, PBL won't succeed, insisted Borchardt. "Your leadership team has got to be behind it and you've got to have ongoing support well past the initial training," she said. "The fact that our superintendent and the whole team was totally in support of doing project-based learning speaks volumes about the success that we've had in our district." She noted that the superintendent is still an avid supporter. In fact, two of five goals set for him by the board "are related to PBL."

Martinez's Draper concurred; leadership has made all the difference. "When Superintendent Deirdre Pilch [joined the district] five years ago, she said, 'I want you to look deeply at who your students are and what you need to do, and then I want you to do that.' That opened the door," Draper explained. "That's when it started to change here, because we were given permission to really be the professionals that we are and look at our kids and ask, 'What are the assets that they bring? How can we enhance what they already know and are capable of doing? And how can we get better achievement for them?' Every one of my kids is going to leave me knowing how to learn and knowing that they are strong students"

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.