Cybersecurity

LAUSD Ransomware Attack: A Wake-Up Call for Policymakers?

Knowledge and Attention Are Not Lacking Among K-12 IT Practitioners; Resources and Oversight Are, Experts Say

- By Kristal Kuykendall

- 09/08/22

Describing the Labor Day weekend ransomware attack and response at Los Angeles Unified School District, Superintendent Alberto M. Carvalho, during a Tuesday press conference, referred to the events as “unprecedented.”

Unfortunately, ransomware attacks at school districts are not at all unprecedented: Hundreds of K–12 school districts have publicly disclosed ransomware attacks since 2016.

That’s likely just the tip of the iceberg, too, cybersecurity expert say; most states do not require public schools to disclose cyberattacks, let alone the ransomware incidents.

With no mandated reporting of cyberattacks, school districts do not disclose cyberattacks more often than they do, according to K12 Security Information Exchange, the nation’s only nonprofit organization dedicated solely to U.S. public schools’ cybersecurity.

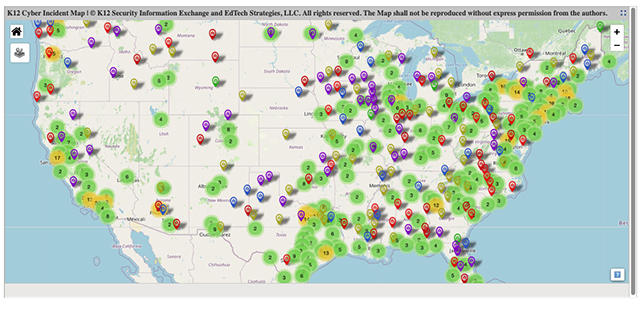

Ransomware — which typically cripples targets’ digital systems — has taken over as the most common type of cyberattack disclosed by public schools, K12SIX said in its State of K–12 Cybersecurity Year in Review report released in March. The nonprofit’s K–12 Incident Map has documented over 1,300 publicly disclosed cyberattacks against U.S. school districts since 2016, scores of which used ransomware.

Ransomware attacks are the most expensive for school districts and the most dangerous for students and staff: Ransomware exists to steal private and sensitive data before the victims even know they’re being targeted, and then attackers extort money for said data. Ransomware is the hardest type of cyberattack for school leaders to keep private.

Last year, 62 ransomware attacks were publicly disclosed by U.S. K–12 school districts, the report said. Every week, a school district somewhere in the United States is hit.

Unprecedented? Hardly.

What was unprecedented was the immediate aid and resources from every level of law enforcement — all the way up to the FBI, the National Security Agency, and even the White House.

Los Angeles Unified School District, with 540,000 students enrolled and 70,000 employees, is the largest school district in the nation to have experienced a ransomware attack — that the public knows about, at least.

Carvalho, who joined LAUSD in February after 13 years as superintendent at Miami-Dade County Public Schools, noted during Tuesday’s press conference that the aggressive and immediate response from local, state, and federal law enforcement and cybersecurity experts was key to avoiding a district-wide catastrophe.

“It’s undeniable that if we had not detected this anomaly and responded by alerting our law enforcement partners, and brought in all the expertise that we brought on board so quickly, it could have been a catastrophic set of circumstances that we would be facing today,” Carvalho told reporters. “Just consider this: If we had lost the ability to run our school buses, over 40,000 of our students would not have been able to get to school. If our Food and Nutrition Service had been disrupted, or if our payroll system had been disrupted, the implications on the lives of students, the lives of the workforce in this community would have been significant, very disruptive, and debilitating to our school system.”

Also unprecedented: By noon Tuesday, every mainstream news outlet in the world was talking about the ransomware attack and K–12 cybersecurity concerns — and the need for more resources for public schools to protect themselves.

That discussion ramped up further later Tuesday when the FBI, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center issued an urgent Cybersecurity Advisory warning that the Vice Society ransomware group has been targeting education organizations far more frequently than other sectors in recent months.

Vice Society is relatively new in the cyber threat universe, having first been identified by security experts in early summer 2021. Through mid-June of this year, the gang had claimed responsibility for 88 ransomware attacks, all of which are still listed on its dedicated data leak site, according to the technical analysis cited in Tuesday’s federal Cybersecurity Advisory.

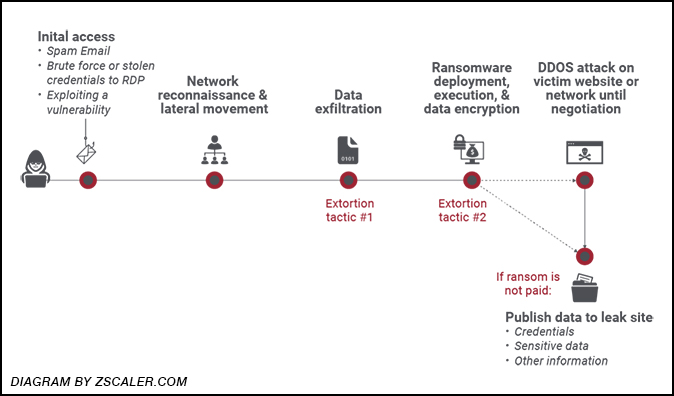

The group is known for its double-extortion tactics — meaning it sneaks onto victim servers, copies the private and sensitive data, then locks up the systems, encrypts the victim’s data, and demands a ransom payment. If the ransom is not paid, the attackers typically sell the private data on the dark web or publish it on public websites in an effort to embarrass the victim. A diagram by information security website Zscaler.com, pictured below, illustrates the typical progression of ransomware attacks.

Doug Levin, national director at K12SIX, tracks cyberattacks targeting K–12 schools; his research and frequent discussions with administrators and IT practitioners at public schools form the basis of the nonprofit’s annual cybersecurity reports, its K–12 Cyber Incident Map, and its free advisory services and cybersecurity resources for schools.

“I can confirm that Vice Society is among the most active ransomware gangs targeting U.S. school districts, and not all their attacks have been publicly disclosed,” Levin told THE Journal this week. “Among the school districts that have disclosed ransomware attacks perpetrated by Vice Society are Frederick Public Schools in Oklahoma, Whitehouse Independent School District in Texas, Manhasset Free Union School District in New York, and most recently, Linn-Mar Community School District in Iowa last month.”

Although Carvalho did not directly point the finger at Vice Society in statements about the LAUSD attack, the fact that the FBI, CISA and MS-ISAC issued the Cybersecurity Advisory within 72 hours of coming to LAUSD’s aid “certainly suggests that Vice Society may have been responsible for the ransomware attack on LAUSD,” Levin noted.

“Nonetheless, the general advice the advisory offers to other districts is sound — and consistent with advice given for some time now by the federal government and others — including K12SIX in its Essentials series,” he said. Such guides for K–12 schools’ IT leaders specify a handful of controls that, if implemented, would make an “enormous difference” in schools’ defensive posture.

“But let's not miss the forest for the trees here: The challenge is NOT that experts don't know what to do. The challenge is that there are precious few incentives for superintendents, school boards, and policymakers to take the issue seriously,” Levin said. “This should serve as a clarion call for superintendents, for school board members, for policymakers that schools are being victimized here and they need more and better support immediately — it can happen to anybody from the smallest to the largest school districts.”

Others, too, framed the LAUSD attack as a much-needed turning point. Los Angeles Police Chief Michael Moore, during Tuesday’s press conference with the LAUSD superintendent, called cyber threats the “No. 1 threat to our safety: an invisible foe and a tireless foe.”

“This is a wake up-call ... because all of us are so dependent on our cyber universe,” Moore said. “Personal businesses, public and private sector are constantly being probed and constantly under attack. And that is why it's critical that you pay attention to your security systems, that you pay attention to who your users are, and that you're constantly on vigilance.”

Levin said IT practitioners at the nation’s public schools don’t need wake-up calls — they need resources and a national commitment to help them keep schools protected.

“There are no federal laws that guarantee a minimum duty of care, and precious few state laws — and none of those provide resources for implementation,” he said. “This despite nearly 40 years of federal and state education policy pushing schools to modernize and adopt technology — all in an effort to be both more effective and efficient.”

The K–12 Cybersecurity Act report and recommendations were supposed to come out in February or March and have yet to be released, Levin said, noting the apparent lack of urgency among policymakers.

Aaron Sandeen, CEO of Cyber Security Works, agreed that schools need help immediately.

“Lack of resources and funding, combined with the usage of legacy systems, is enabling cyberattackers to disrupt the day-to-day operations of schools while stealing valuable information to ransom them for amounts that the schools could ill afford,” Sandeen said. “Ransomware incidents cause significant damage in terms of finances, reputation, and data security. In 2021, U.S. schools lost $3.56 billion due to ransomware attacks, and it led to the shutting down of two educational institutions for good. LAUSD seems to have minimized disruption, but it is certainly another reminder of what schools are up against.”

Meanwhile, Levin said, it is students, families, teachers, and taxpayers who are “left twisting in the wind.”

“The superintendent of LAUSD may be able to call on the White House for help with incident response; that's not the answer for the thousands of other U.S. school districts facing these same risks everyday.”