Is Your OS XP-ired?

New minimum requirements for assessment have district leaders talking about technology. As they consider upgrades, they should plan not just for testing, but for teaching.

- By Geoffrey H. Fletcher

- 02/12/13

Bob Staake

|

The names of operating systems and devices have been on the lips of unlikely people lately.

For the past six months or so, phrases like "XP versus Windows 7," "iOS5 versus iOS6.x," and "iPad 1 versus iPad 2" have been uttered by superintendents, state commissioners of education, and even state legislators. In this day and age, these leaders certainly should understand and care about technical details, but I am just not used to hearing such things from them.

The reason for the conversation, of course, was the looming question of what systems and devices would be declared allowable for new assessments from the Race to the Top assessment consortia, Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium and the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC).

At least part of the answer arrived on December 4, when Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) released "The Smarter Balanced Technology Strategy Framework and System Requirements Specifications." As of press time, PARCC has not yet released its requirements, but all indications are that they will not differ significantly from those of Smarter Balanced. Both consortia are reserving the right to alter some parts of the specifications, especially those related to networking and bandwidth, but the short answer to the operating system question on policymakers' minds is that Windows XP will meet the minimum requirements for the Smarter Balanced assessment. iOS5 and the iPad 1 will not, due to the lack of security safeguards.

Apple addressed these security issues in more recent hardware and software, so the iPad 2 with iOS6.x and other tablets with similar specs will be allowable for the Smarter Balanced assessment (and undoubtedly for the PARCC assessments as well). The iPad mini and other tablets with screen sizes smaller than 9.5 inches do not meet the requirements.

But don't stop reading, because the answer to the question has not solved the problem.

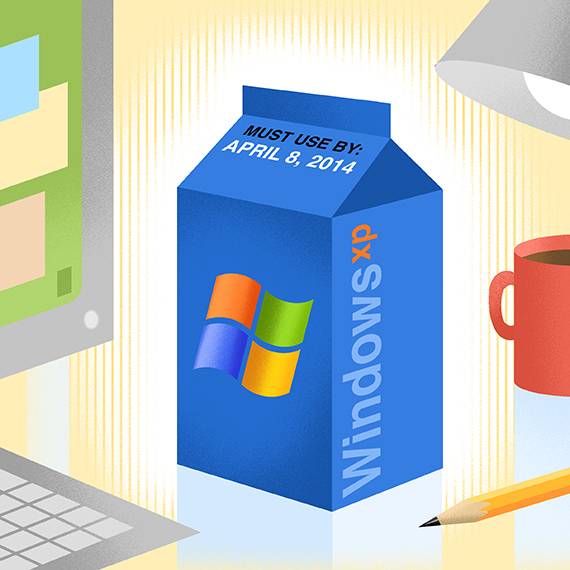

Software With an XP-ration Date

The XP dilemma is important to policymakers because of information from a report prepared by Pearson for the consortia. Based on data collected by the Technology Readiness Tool (TRT) prior to July 15, 2012, the report includes input from 11,789 districts and 56,268 schools, representing nearly six million devices. That is by far the largest aggregation of device-level data ever gathered. No, the full report is not available to the public and yes, there are some discrepancies in the data. Nonetheless, as Smarter Balanced notes in the report, "...the overall trends presented are valid and persistent across states due to the overall size of the sample."

One key data point is that 56.1 percent of the devices entered into the database use Windows XP as their operating system. This figure led the consortia to decide that that their technology-based tests could be operated on devices with XP--otherwise, they would have had to require more than half of the devices in schools across the country to upgrade or be replaced. That would be no small expense, and who would pay for it? Would it be the federal government (which provided the money to the consortia and encouraged "next generation testing")? Would it be states and their departments of education that are members of the consortia? Would it be the school districts who administer the tests? "Who would pay for an XP upgrade?" has been the proverbial elephant in the room for more than a year. Now many leaders may breathe a sigh of relief, safe in the knowledge that they can keep their XP devices a little longer and spend the few dollars they have in their technology budget on other things.

Case closed, right?

No, because Microsoft has made very clear for more than a year that it will stop supporting XP by 2014. That means no more security patches, theoretically leaving more than half of the devices in US schools significantly more vulnerable to viruses, breaches, or any other security threat.

Looking Beyond Assessment

The focus on operating systems and devices for the new assessments, however, obscures a much larger reality: educators need to be thinking about technology for much more than assessment, a point that this column has tried to make since its inception. The State Educational Technology Directors Association (SETDA) has also advocated for a broader view of technology. In that spirit, SETDA released a document, "Technology Readiness for College and Career Ready Teaching, Learning and Assessment," on December 4, the same day that Smarter Balanced released its framework and specifications.

The release date was not a coincidence. As the SETDA document notes, the minimum technology specifications laid out by PARCC and Smarter Balanced are only part of the picture. Schools still need to weight high-stakes assessment needs against the full range of technology issues they're addressing today. To both consortia's credit, they have made similar points time and again, almost since the day they started work.

To wit (from SBAC): "The specifications described in this document are minimum specifications necessary for the Smarter Balanced assessment only. Minimum specifications to support instruction and other more media-heavy applications are higher than those necessary for the assessment." In other words, the difference between minimums for high-stakes online assessment and minimums for teaching and learning with embedded assessment creates some very specific considerations for infrastructure, devices, people, and long-range planning and budgeting. The difference between the two forms the core of SETDA's document.

The most obvious of these infrastructure considerations is bandwidth. Smarter Balanced estimates that its assessment will require 1 Mbps per 100 students to work effectively. "The Broadband Imperative," a SETDA report released in May 2012, estimated that schools will need ten times that capacity for teaching, learning, administration, and assessment. Schools also need to pay attention to all instructional spaces in schools, because local architecture, server settings, and the number of wireless access points and device types may affect a system's performance in individual classrooms. iPads, for example, may use more bandwidth than other wireless devices.

When saying that XP can be used for their assessments, Smarter Balanced provided a number of caveats. The first of their "district takeaways," which I read as a recommendation, is "Plan to migrate from Windows XP to newer OS within two years of Microsoft's support end of April 2014." The SETDA document points out that the use of computers, servers, and networks more than five years old will increase the chances of disrupted learning, lost productivity, and a "dramatic escalation in security and software incompatibility issues--as well as increased odds of hardware failure." To paraphrase Nancy Reagan, just say no to XP by 2014.

Supporting teachers is the key to implementing all of this, especially since they are the ones called on to implement the Common Core State Standards. The standards require a new approach to instruction for many teachers, including, as the SETDA technology readiness document notes, "the integration of new instructional materials and teaching tools. Professional development must assist teachers to make these instructional transitions with technology and not treat technology-related professional development as distinct from the instructional process."

Likewise, schools need an adequate number of support personnel to ensure that the technology works. An industry (not education) standard is one support person for every 65 devices. Even though schools--where there are different operating systems, different versions of software, and more than one person using most devices--arguably require more tech support than most private- sector businesses that have much greater standardization, 1-to-65 is a still very high bar for education as an industry. Nonetheless, it's a bar we must get under. We have no choice anymore.

Finally, there is long-range planning and budgeting. The SETDA technology readiness document recommends that technology costs be included as an ongoing line item in annual budgets, and notes, "Schools spending less than 5 percent of their budgets on devices and infrastructure will be hard-pressed to meet existing and future needs. " For a district spending $10,000 per student, budgeting $500 per student to provide a device, to build and maintain internal networks, and to have a connection to the internet is not too heavy a lift. SETDA offers a variety of sample strategies to repurpose existing funding streams and to plan for recurring costs. These strategies include pursuing joint purchasing agreements for lower pricing, repurposing traditional textbook spending as detailed in another SETDA report, "Out of Print"; considering open source software and open educational resources; and looking at leasing equipment.

While it is a step in the right direction for our education leaders and policymakers to be thinking about operating systems, a crucial next step is for them to consider the neccessity of technology in all facets of education. Technology-based assessment is an important piece of the puzzle, and if it can be a driver toward the ubiquitous implementation of an appropriate technological infrastructure for education, all the better.