Robots Rule as Competition Season Heats Up

Worldwide competitions dominate robotics news in April. But Team Antipodes (tagline: "One Robot to Rule Them All...") has gone as far as it chooses to. Although it will attend the FIRST Championship with its latest robot, Archie (short for Archimedes), taking place in St. Louis at the end of April, the three young women who make up the team expect to spend a lot of their time meeting up with friends and cheering each other on.

Antipodes, headquartered in Pacifica, CA, has had a good run in its four years of operation. Terra Nova High School juniors Kjersti Chippendale, Emma Filar, and Violet Replicon have taken second place in the Northern California FIRST LEGO League (FLL) championships; traveled to the Open European FLL competition in Istanbul, Turkey; won the Tasmanian State FLL contest on a joint Australia/United States team; won the Robocup Junior Dance Theater World championships; won the Colorado State FIRST Tech Challenge (FTC); and competed in the World Championships in St. Louis.

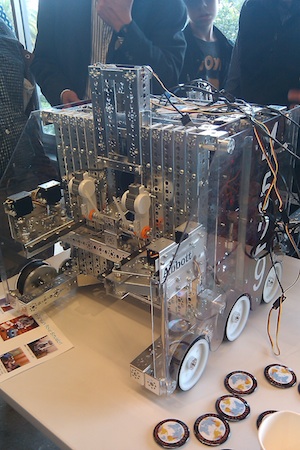

Antipodes robot Archie on display |

During the FTC competitions, one alliance--made up of two teams--competes against another alliance to put their robots through various paces. The game includes both driver-controlled periods and autonomous periods. The object of the game is to score more points than the opposing alliance. For example, Archie's duo will maneuver around obstacles while scooping up racquetballs, determining whether they're made of magnetic material or not, and sorting them into stacking ball crates. The higher the crates with balls are stacked, the more the points stack up too. On certain parts of the "field" robots are encouraged to knock over the opponent's crates. For the fun of it, the field also includes two six-pound bowling balls that can be parked in various spots on the playing field (a 12-foot by 12-foot diamond) for extra points.

Coach Ken Filar, Emma's dad and an architect, learned about robotics when he went to an event at a San Francisco-area NASA site. "There was a little robot demonstration going on with girls from a FIRST Tech Challenge," Filar recalled. "I walked by and started talking to them. The kids worked their magic on me. They said, 'You should become a coach and start a team.'" And he did. The effort calls for the students to work four or five hours a week on their robot; that commitment grows to three or four times as much as the date for a competition approaches.

The girls have learned programming and computer-aided design; how to work with band saws and other tools; and how to use a whiteboard to figure out problems. A couple have spent a semester in Australia as exchange students, they've hosted their own Tasmanian friend; they've made presentations to their school board, at Google, and at other gatherings; and they've become dedicated to sharing their experiences and mentoring younger robotics teams, particularly other all-girls teams.

The Robotics Phenomenon

Robotics in K-12 has become a phenomenon, with multiple organizations--FIRST, VEX, BEST, and Botball--selling kits, encouraging students to participate, and running competitions. During 2012, FIRST competitions will encompass nearly 27,000 teams with 293,000 high school, middle school, and grade school students. The VEX program, run by VEX Robotics Design System, hosts 4,800-plus teams in 23 countries and puts on 300 events a year. The VEX world championship takes place in Anaheim starting April 18 and will host 600 teams from 17 countries.

Yet, with all of this activity, these programs combined are only in 10 percent of the schools in the United States, according to Jason Morrella, president of Robotics Education and Competition Foundation, a non-profit started by VEX that supports robotics and technology events and programs. These programs "don't compete with each other," he insisted during a recent talk given during a robotics event hosted by design software company Autodesk. Some programs require the robots to be programmed, others use remote control, and still others use a combination. The cost of the robotic kits varies, depending on how sophisticated the machines are, what size of team it requires, and how long it takes to build.

Morrella noted that robotics can be added to classroom activities with curriculum that meshes with math standards from multiple entities, including Autodesk, intelitek, Carnegie Mellon Robotics Academy, and Project Lead the Way. But just as many school robotics teams are hosted by parents or companies and delivered as extracurricular programs.

Either way, students "learn problem solving, design work, teamwork, leadership," Morrella said. "When I was teaching, the best thing I would see the students get out of the program by the end of the year wasn't the science that they learned. It was the problem solving, the team work, the time management skills, the anger management skills--not getting their way, having to brainstorm, having to use other people's ideas. That's valuable stuff for students to get used to in middle school and high school to prepare them for college and a career."

Team Antipodes at a middle school career event |

A Channel to Creativity

What Chris Bradshaw said he values about robotics programs is how they inspire creativity. Bradshaw is Autodesk's chief marketing officer and senior vice president for "reputation, consumer & education." That includes oversight of an education community program that provides Autodesk software to students anywhere in the world for free.

Initially, Autodesk's computer aided design programs were popular in post-secondary environments, said Bradshaw. "We've been slowly backing up--going younger and younger. We really span the spectrum now of the smallest kids to oldest kids." For example, the company offers TinkerBox, a free physics puzzle game for computers and mobile devices that teaches science and basic engineering concepts. It's most popular, he noted, with nine-year-old boys.

"One of the biggest complaints we get from our professional customers is that when they go to hire, the kids coming out of college have degrees, they're smart, but they don't have a lot of creativity," Bradshaw said.. "We're training kids from five or six years old to believe that every answer is either A, B, C, or D--one of the circles. [During] most all of K-12 and college, you're filling in dots that say, 'There is one right answer to this question.' When you go to these robotic competitions and you see every team with the same kit and same instructions and competing with the same rulebook, there will not be even two robots that look even remotely alike. This notion of A, B, C, or D evaporates in this environment. You get kids learning that many solutions are possible. Many solutions work."

STEM Connection

Then there's the STEM connection. According to research done a decade ago by Brandeis University, FIRST participants are twice as likely to go into science and engineering majors. Female participants are four times more likely to pursue those majors in college.

Bradshaw acknowledged that company support for robotics competitions also makes for good business. "We know most of these kids are potential users of our software in the future in their professional lives. We also know our software can help them today with the design of their robots."

In fact, Antipodes, the all-girl team in Northern California, tapped Autodesk Inventor to redesign Archie to extend higher than it did in its first generation. Whereas the original Archie design included four stages, which reached four to five feet, second generation Archie can reach five to six feet. Although the team is taking a relaxed attitude toward this year's international championship, it knows that the effort to add that additional height will earn extra points for Archie.

After that competition, Antipodes will come home and put on a campaign at the students' high school to attract others to robotics in order to carry on the work they began four years ago.

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.