Research: Video Gamers Learn Visual Activities Faster

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 04/01/15

Score one for gamers. An experiment at Brown University has uncovered a correlation between

people who frequently play video games and their ability to retain learning about two quickly learned visual activities. The results suggest

that video game playing not only improves player performance but also builds up the capacity to improve performance.

According to, "Frequent Video Game

Players Resist Perceptual Interference," a paper recently published on PLOS One, the

researchers ran a small experiment. They had two teams of people, nine frequent gamers and nine non-gamers, participate in two days of

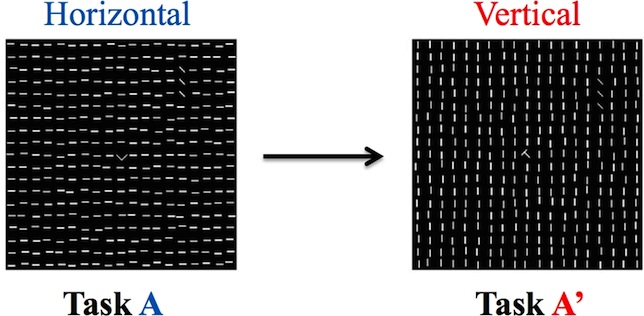

learning activities. Participants were shown an on-screen "texture" of either vertical or horizontal lines. Their job was to point out the area

where an anomalous texture appeared.

Previous research has proven that most people can improve their performance on this type of task, but only if they get sufficient time to

"consolidate" the learning in their minds — presumably to hard-wire the neural connections needed to perform the activity. When they move onto

a second task too quickly, the learning of the first one might be affected. The researchers wanted to figure out if gamers could overcome the

interference more easily.

On the first day, the participants were trained on each of the two tasks (in a random order). On the second day, they did each again — also

in a random order — allowing the researchers to assess whether they had improved, even by milliseconds.

Indeed, the gamers improved their performance on both tasks, while non-gamers improved on the second task they trained on, but not on the

first. For the non-gamers learning the second task interfered with learning the first.

According to the data, gamers improved their combination of speed and accuracy on average by about 15 percent on their second task and

about 11 percent on their first task. Non-gamers also improved performance on their second task by about 15 percent as well; but they actually

did worse on the first task by about five percent.

The researchers said they aren't exactly sure what's happening in the brain of gamers that differs from non-gamers, but according to Yuka

Sasaki, associate professor in the Department of Cognitive, Linguistic and

Psychological Sciences (CLPS) at Brown, the study suggests that gamers may have a more efficient process for hardwiring their visual task

learning than non-gamers. "It may be possible that the vast amount of visual training frequent gamers receive over the years could help

contribute to honing consolidation mechanisms in the brain, especially for visually developed skills," the report stated.

"When we study perceptual learning we usually exclude people who have tons of video game playing time because they seem to have different

visual processing. They are quicker and more accurate," said Sasaki in a statement. "But they may be in an expert category of visual

processing. We sometimes see that an expert athlete can learn movements very quickly and accurately and a musician can play the piano at the

very first sight of the notes very elegantly, so maybe the learning process is also different. Maybe they can learn more efficiently and

quickly as a result of training."

By documenting these and other apparent cognitive differences between gamers and non-gamers, the field is discovering that there is more to

video games than merely passing the time, added Aaron Berard, Sasaki's colleague in CLPS and lead author of the paper. "A lot of people still

view video games as a time-wasting activity even though research is beginning to show their beneficial aspects. If we can demonstrate that

video games may actually improve some cognitive functioning, perhaps we, as a society, can embrace newer technology and media with positive

application."

The researchers offered several caveats regarding the study. First, the small number of subjects in each group limited the "statistical

power" and may have "concealed additional trends in the data," they noted. Second, even in the non-gamer group, many people reported that at

some time in their lives they've played at least one video game and possibly more. "It is possible that these people may have experienced

changes in visual ability due to brief exposure," the paper pointed out. As a counteraction, the researchers divided their test subjects based

on gaming activity in the last six months. Third, there was a definite gender bias between the two groups. The gamers were primarily male; the

non-gamers primarily female. However, the researchers stated, recent data collected for another project "revealed no statistical difference in

behavioral performance trends across males and females." Fourth, because the testing went over two days, some of the participants may have

affected their outcomes by not getting enough sleep, confounding the results.

The researchers will continue their work. What they haven't determined yet is whether playing video games improves learning ability or

whether people with an innate ability become gamers because they do better at it.

The project was funded through National Institutes of Health grants.

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.