Equity Through Access: 21st Century Learning & the Necessity of 1-to-1

The mission of the Partnership for 21st Century Learning (P21) is to promote 21st century innovative teaching and learning through concerted efforts with government leaders, educators, businesses and community members (2015). The student outcomes within the P21 Framework include life and career skills, learning and innovation skills, core subjects and 21st century themes, and information, media and technology skills. Blended learning opportunities that integrate face-to-face teaching and online learning fosters information, media and technology skills, as well as learning and innovation skills or the Four Cs of critical thinking, communication, collaboration and creativity skills. These student expectations within the P21 framework demonstrate the necessity for students to have access to personalized technology in all aspects of learning, both at home and at school (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). School districts have an obligation to provide equitable access to technology in order to close the digital divide and reduce barriers for students while also preparing them for the digital complexities of the future (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). It is essential for all K–12 students to be provided with a district purchased personal device in order to meet the demands of 21st century competencies for everywhere, all-the-time learning as framed in P21.

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) further support this need by including over 100 references to technology expectations, reflecting the significance of blended learning in today’s educational environment (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2017; U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2016). CCSS require students, as early as elementary school, to strategically employ technology to enhance reading, writing, listening, speaking and language skills through the use of multimedia tools, gathering relevant facts from digital sources, accessing credible digital sources and consulting digital reference materials (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2017). For this reason, it is essential for all K–12 students to be provided with engaging teaching and learning experiences in a personalized blended learning environment in order to meet the high demands of CCSS for college and career readiness which, in turn, supports the expectations of P21.

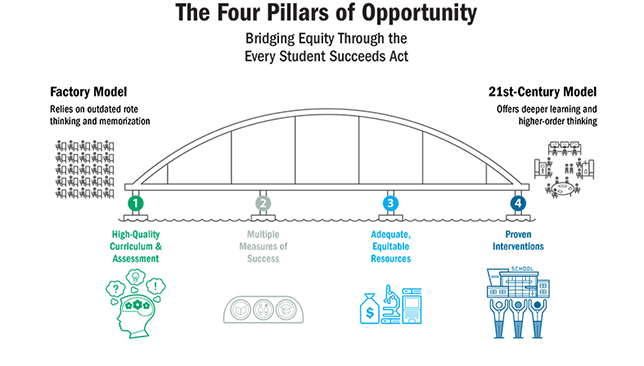

The federal government, in recognition of the importance of P21, has included its tenets in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). In addition to the alignment of instruction to 21st century learning goals, the recent passage of ESSA supports the placement of equity in education at the forefront of federal education policy by including provisions that insist upon states and school districts providing an equitable, high-quality 21st century education for every student. In the legislation, the Four Pillars of Opportunities create a bridge between the traditional one-size-fits-all education model to the 21st century model of deep learning and thinking, which directly aligns with the objectives of ESSA. One specific Pillar of Opportunity, High-Quality Curriculum & Assessment, focuses on developing critical thinking, problem solving and higher order skills, as well as personalizing learning to meeting the needs of each individual student, regardless of race, background or economic status (Cook-Harvey, Darling-Hammond, Lam, Mercer, & Roc, 2016). There are states across the nation, including Vermont, Oregon, New Hampshire and South Carolina, that are at the forefront of developing and aligning College and Career Standards from kindergarten to high school containing skills such as collaboration, communication and complex problem-solving which mirror those in the P21 Framework (Cook-Harvey et al., 2016).

The ESSA pillar of Adequate, Equitable Resources attempts to address the gap in equity of resources across schools. To address this issue, grant opportunities under Title IV of ESSA, target effective use of innovative technology. In addition, there is a concerted effort to increase the purchase of personalized devices, support technology integration and increase personalized blended learning by providing experiences that are more individually relevant and engaging to students (Cook-Harvey et al., 2016; Mesecar, 2015; U.S. Department of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2016).

According to ESSA, it is imperative that states, districts, and schools provide equitable teaching and learning opportunities which address high order thinking skills through collaboration and communication, as framed in the P21 Four Cs of collaboration, critical thinking, creativity and communication (Cook-Harvey et al., 2016). Equal access and equity of technology and resources are a necessity for personalized blended learning, so that each and every student in the nation can take greater ownership of their learning and is better prepared for the unprecedented opportunities of the 21st century.

The Four Pillars of Opportunity (Cook-Harvey et al., 2016)

Historically, legislation addressing equity and fairness in public education has been an issue of importance (Rose, 2014). In 2007, the International Association for K–12 Online Learning (iNACOL) advocated for equity in online programs, resulting in the development of standards to support leaders and policy makers in ensuring high quality online education programs. The iNACOL publication, Access and Equity in Online Classes and Virtual Schools, increased awareness and addressed issues of legal obligations for accessibility to online learning (Rose & Blomeyer, 2007). The standards delineate the roles of instructors, course designers and program administrators sharing the responsibility as technology leaders, to support the goal of equitable educational opportunities. These policy and leadership responsibilities have continued to evolve and multiply with new teaching pedagogy and the expansion of various blended learning models bringing everywhere, all-the-time learning to a reality for all learners.

Denying students educational opportunities and resources is an ethical concern in all aspects of public education. Digital equity is now being viewed as a civil rights issue within the current digital era (Schwieger & Rivereo, 2016). A commitment by local school districts to act now and deploy 1-to-1 devices ensures that all students will have equitable access for high quality digital learning, regardless of ability, economic circumstance, location or cultural background (Callaghan, Costa, Roberts, Andrews, & Dach, 2013). Technology has the power to transform education, and is seen as a right to be afforded to all students in order to level the playing field (U.S. Department of Education, 2010).

The National Education Technology Plan (NETP) is a guiding document for systemic change to support this vision in education today (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). Recent NETP updates released by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Technology call for the effective use of technology, also addressed in Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Originally the 2010 NETP delineated the urgency for advanced technology in order to motivate, engage and empower students, as well as provide personalized learning utilizing the Universal Design for Learning model (Curran, 2015; Transforming American Education, 2010). The latest update recognizes the need for equity in transformational learning experiences for all students and anytime, anyplace learning as well as a greater emphasis on personalized professional development for staff to build visionary technology leaders across the United States (U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2016).

The five overarching components of the National Education Technology Plan were devised as guidelines for state, districts and federal government leaders, as well as administrators and teachers, in order to enhance the core of learning, powered by equity in technology innovation (U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2016). The most recent component and goals include:

- Learning: Learning must be engaging and personalized with greater equity in high-quality teaching and learning opportunities through blended learning models. Students need to be empowered to make choices in their learning as a foundation for the future.

- Assessment: Meaningful assessments utilizing digital tools for feedback and reflection increases versatility and may be creatively employed throughout the learning process to make results more effective, accessible and valid for teacher and student improvement. Digital assessments are embedded in learning, adaptive and enhance personalized learning while at the same time protect student data and privacy.

- Teaching: Teaching with technology calls upon teacher preparation programs to rethinking training. Technology in teaching allows for ongoing access to student data, collaborative learning communities, support for teachers and students, as well as resources for increased creativity and innovation. Collaboration beyond the school walls for anytime, anyplace learning is critical.

- Infrastructure: Comprehensive infrastructure for learning must be robust with access to high-speed internet and resources for management and maintenance. Responsible Use Policies are developed based on district policies and guidelines, in addition to protections for student data and privacy.

- Leadership: Leaders need to create a shared vision and collaborate with all stakeholders and organizations to develop implementation goals. It is important for leaders to provide ongoing personalized training to equip teachers as instructional designers, facilitators and coaches so they can successfully personalize learning.

The National Education Technology Plan embeds the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in a blended learning environment to provide equitable access to quality instruction for diverse needs and shares the vision of urgency for all stakeholders to prepare 21st century innovative thinkers for a technology-driven future (U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2010, 2016). Professional development models including peer collaboration and coaching as well as authentic opportunities for guided practice, exploration, application and reflection. The models of professional development for educators are enhanced through technology supporting innovation in planning, designing and refining instruction meeting the expectations of the National Educational Technology Standards and also providing a vast range of experiences for teachers as they construct their own knowledge (Kassner, 2013; McCann, 2015; Wyndham, 2010).

The UDL framework identifies a shift in the goal of education from simply gaining knowledge to the process of expert learning (Gordon, Meyer, & Rose, 2014). UDL recognizes the three interconnected brain networks which account for differences among learners: recognition networks, strategic networks and affective networks (Evans, 2014). Understanding these three networks is essential in identifying strengths and weaknesses within learners and ways to address their diverse learning needs through effective curriculum planning resulting in maximizing instruction. The recognition network, or the “what” of learning, allows the learner to identify and interpret sound, taste, sight and touch to focus on gathering facts. Working in conjunction with the recognition networks are the strategic networks, or the “how” of learning, which allows the learner to plan and monitor skills. Finally, the affective networks, or the “why” of learning, drives motivation and engagement in learning with relationship to the emotional connectedness in the learning process (Evans, 2014). By understanding the brain networks within learners, educators can take into consideration the individual needs of learners, the objectives of the curriculum and the method of instructional delivery in order to remove potential barriers to learning (Evans, 2014). The guiding principles of UDL focus on multiple means to represent content, increase student engagement within the content and express understanding of content. These principles also identify the necessity for student choice in expressing understanding through technology.

Digital learning has direct implications on effective implementation of UDL to support differentiation in content, process and product (McCann, 2015; Tomlinson & Mctighe, 2006; Wyndham, 2010). Twenty-first century digital tools allow for diversified instruction designed around delivery, connectivity and experiences so students are empowered through collaborative engagement, participation and creation (Evans, 2014). A study conducted by Wyndham (2010) concluded that administrators and teachers receiving UDL training, compared to those who did not receive training, employed greater use of technology within their instructional practices which allowed for student choice, flexibility and increased access to curriculum.

The Consortium for School Networking (CoSN), a national association of technology leaders that promotes innovation and personalized learning, created an Action Tool Kit advocating for student access to technology beyond the school day for everywhere, all-the-time learning (Schwieger & Rivereo, 2016). This underlying expectation neccesitates a district-provided personal device to bridge the learning and homework gap, especially for low- income families who may not have access to a personal device within the home. A CoSN Task Force explored the homework gap and concluded that the greatest impact was to low-income black and Hispanic students who lacked home access to high speed Wi Fi and a personal electronic device (Schwieger & Rivereo, 2016). It was found that low income parents were less engaged in monitoring homework and less able to receive electronic school notifications due to limited digital access, while their children were less apt than peers to complete digital nightly homework assignments. As a school community, providing a personal device for student access during the day and after achool hours also benefits parents, as they are given the means to monitor and increase their engagment in the academic performance of their child. According to Schwieger and Rivereo (2016), it is the responsibility of community partners, non profit organizations and agencies to develop digital equity strategies beginning by understanding the depth of the issue in order to identify resources and systems to address these needs. Today there are leaders and innovators across the United States addressing digital equity as a priority (Andover Public Schools, 2015; Bebell & Burraston, 2014; Hanover Research Council, 2010; Schwieger & Rivereo, 2016).

An exemplar of one such innovative technology project is Eliminate the Digital Divide (E2D), in Davidson, NC. The project was initiated by a young student within the school district who was inspired to make a change for students in the community supporting the vision of decreasing technology inequity. E2D was awarded the 2015 Next Century Cities Digital Inclusion Leadership Award for community innovation and commitment by providing a computer and internet access for every school-aged student in the district through fundraising efforts and engaged community action. The support and buy-in of the Davidson City Mayor was instrumental in the success of this initiative, proving the importance of stakeholder collaboration. The intentional shared commitment to make digital equity a reality is essential today in the digital era (Schwieger & Rivereo, 2016).

While great benefits have been documented by providing every child access to devices, district-wide deployment of devices opens the door to concerns of internet safety and student privacy (U. S Department of Education, 2016). Federal and state laws have specifically addressed these concerns with the goal of protecting students who are accessing the internet in a digital learning environment. The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) prevents software companies from tracking student’s personally identifiable information if the student is under age 13, unless parental consent is obtained, in order to maintain confidentiality and security (U.S. Department of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2014). Additionally, The Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA) requires school districts and public libraries that receive internet access at discounted rate through the federal E-rate program to filter or block inappropriate online content for minors (U.S. Department of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2014). CIPA also stipulates that school districts must inform students about digital citizenship expectations, while Title II of the Broadband Data Improvement Act requires minors to be educated about social networking and cyberbullying (Bosco, 2011). It is essential that federal and state legislation construct a legal framework for individual school districts to follow as they directly address filtering, privacy, safety and AUP issues through the development of new policies and procedures.

A policy guide developed by CoSN reiterates the necessity of a safe digital learning environment in schools where students access multimedia resources through the internet (Bosco, 2011). This comprehensive policy guide is based on federal legislation and state law with the goal of guiding district decision makers through the development or revision process of digital media policies and procedures. According to CoSN, Acceptable Use Policies (AUPs), otherwise referred to as Responsible Use Policies (RUPs), are signed by students, parents and school personnel outlining expectations and violation consequences for digital use (Bosco, 2011; U.S. Department of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2014). AUPs have a two-fold responsibility to protect students from harmful content on the internet and also provide access to digital media to support personalized learning (Bosco, 2013; U. S. Department of Education, 2014). AUPs are pivotal in providing a reader-friendly written agreement between all stakeholders clearly stating expectations, academic integrity and consequences for violations with the goal of teaching and developing responsible digital citizens in a connected world (U.S. Department of Education, 2014).

CoSN shares exemplar AUPs within the policy guide, reflecting the variations in policies with differing stipulations and permissible behaviors across the nation. District-provided devices are the true path to 1 -to-1 initiatives. The National Education Technology Plan cautions against Bring You Own Device (BYOD) programs in schools due to limited control of security features and overly strict policies that have negative unexpected outcomes (Education, 2016). It is advantageous for local decision makers to utilize research and various policy stances to drive the development of AUPs supporting ethical and social responsibilities in their own unique digital context.

Explicit instruction in digital citizenship cultivates the acceptable use of technology within a digital learning environment. The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), a leading organization advocating for educational technology, has developed student, teacher and administrator standards to drive and guide the transformation of education in a digital environment (Callaghan et al., 2013). The expectations for students include demonstrating innovation and problem solving skills utilizing technology in order to communicate, collaborate and build global awareness. The organization recognizes the urgency to develop digital citizenship skills within students, as well as constantly changing and revising these expectations based on advancements in the field.

More recently, the 2016 ISTE Technology Standards for Students revisions embed digital citizenship skills within Standard 2, guiding privacy rights, social interactions online, responsibility and ethical behavior (ISTE, 2016). The standard clearly states, “Students recognize the rights, responsibilities and opportunities of living, learning and working in an interconnected digital world, and they act and model in ways that are safe, legal and ethical” (ISTE, 2016, p. 14). Previously, the digital citizenship standard within the ISTE National Technology Standards for Students was focused more generally on students understanding legal and ethical behavior in a connected world. This future-focused approach, with the refresh of standards, signifies the advancement and potential of educational technology integration as students collaborate with global audiences launching ethical and legal behavior to the forefront of importance (ISTE, 2016).

While AUPs serve a purpose at the district level, students need to directly have the tools to make good digital choices at school and at home, which is accomplished through digital citizenship skills. Common Sense Education, a leading nonprofit media and technology organization, empowers educators, families and policy makers to promote safe and responsible technology use in a positive school culture (2016). Digital citizenship skills, critical thinking, ethical discussions and decision making are embedded within the digital curriculum and comprehensive multimedia resources. The underpinning of a community approach is reflected throughout the scope and sequence specified by grade bands and transferred to cross curricular application with family engagement opportunities. Taking a proactive approach, the engaging interactive tools provided by Common Sense Education support responsible use of technology in developing skills related to internet safety, information literacy, digital footprint, self- image and identify, privacy and security, cyberbullying, communication and copyright within the home and school community. These important skills empower students to make appropriate choices within the school environment and then independently apply them to other environments outside the school walls. Common Sense Education offers certification programs to recognize school districts and communities working proactively to innovatively teach digital citizenship skills. A cornerstone of any educational change is stakeholder buy-in. Without it, groups can become disenfranchised and oppositional.

There are many districts that have effectively included stakeholders in the planning, implementation and delivery process of successful district-wide 1 -to-1 deployment. The Andover Public Schools 1 -to-1 iLearning Initiative (2015) has been proactive in promoting collaborative stakeholder involvement. Framed in research from the Partnership for 21st Century Skills, the vision of this initiative provides device equity and promotes parents’ education on the rationale for 1 -to-1 technology with embedded strategies to enhance personalized learning in a safe, ethical and responsible environment. The full year implementation timeline includes a vast array of informative opportunities for stakeholders, including a parent town meeting, parent device overview, advisory committee meetings, open house, student lead showcase, parent talk series and a parent orientation with policy and handbook review (Andover Public Schools, 2015). From the initiation of the plan, the advisory group included parents and valued open communication as a critical component of the collaboration process to prepare students for the future, while working side by side with the community. Andover Public Schools is an exemplar of a district thinking about innovative and transparent ways to accomplish their technology vision while effectively placing utmost importance on community involvement.

The reengineering of a traditional classroom into an innovative digital learning environment has sparked new thinking in the field. Leading publications by the U.S. Department of Education, NETP, Project RED and ISTE directly address the necessity of the involvement of stakeholders and their participation in the transparent vision setting process of 1 -to-1 initiatives (Crichton, Pegler, & White, 2012; Greaves, Hayes, Wilson, Gielniak & Peterson, 2010; ISTE, 2014; U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology, 2014). Leading national organizations have allocated time, research and financial support to assist districts in effective technology implementation. The Verizon Mobile

Learning Academy (VMLA), endorsed by ISTE, offers a free 10-week course that delivers the ideal support to build a collaborative technology integration vision for a school or district with multiple training options, such as webinars and asynchronous coursework (ISTE, 2014). ISTE recommends for school teams to apply to VMLA, including the school administrator, technology coach and a teacher providing for a more comprehensive understanding of pedagogy, learning context, devices and social interactions within a digital environment. Planning assistance for digital deployment is offered by sharing the phases of implementation in a webinar titled Lead & Transform. Utilizing the expertise of other districts, digital resources and ISTE’s Essential Conditions set the foundation for a visionary plan with robust implementation (Sykora, 2014). It is evident that the partnerships of leading organizations and their research publications will be critical tools in designing collaboration among all stakeholders for future vision in district-wide technology initiatives.

Project RED, a large-scale national research project, studied effective schools with 1-to- 1 initiatives, recognizing the demands of fast paced technology implementation and the challenges confronting teachers and leaders (Greaves, Hayes, Wilson, Gielniak, & Peterson, 2012). Research indicates many teachers struggle to keep up with the ever-changing technology context and the rigorous curriculum demands, placing greater importance on effective teacher preparation in order to select, evaluate and use appropriate technology and resources to personalize learning (King, South, & Stevens, 2016; Lambert & Cuper, 2008). Integrating collaboration, creativity, critical thinking and communication as 21st century skills into a highly engaging blending learning models adds to the complexity of teacher expectations (Hutchison & Woodward, 2014). Technology is transforming teaching and learning in schools today, which also poses new challenges to educators.

Project RED examined both the financial impact and student achievement in transforming education through 1 -to-1 implementation (Greaves, Hayes, Wilson, Gielniak & Peterson, 2010). Together Project RED and NETP reiterate the need for school districts to develop a long-term strategic vision involving all stakeholders in the financial commitment for technology and the robust infrastructure to support effective 1 -to-1 implementation (Crichton, Pegler, & White, 2012). Creative funding for staffing models, applying for loans and grants, and developing community campaigns are all vehicles to fund technology procurements. Learning management systems and digital resources also proved to drastically reduce paper and textbook costs, providing additional funds for long-term device purchases. Results from Project RED indicate that providing a device for every student, coupled with effective instructional initiatives and leadership, allow for daily seamless technology integration increasing attendance, academic achievement and provide financial benefits. Research studies across multiple grade levels conclude that 1 -to-1 device deployment lays a solid foundation for teachers to meet national standards, curricular demands, and personalize learning for the diverse needs evident in digital age classrooms (Imbriale, 2013; Moore, Gillett, & Steele, 2014; U.S. Department of Education, 2016).

Today ESSA continues to drive personalized blended learning and technology integration initiatives forward with the new flexible block-grant program. Allocated funds through these grants will be transferred to states allowing districts to personalize expenditures that enhance ed tech program initiatives aimed to close the achievement gap (Wegner, 2015). Coupled with the E-rate program which reduces costs for district internet access, ESSA encourages innovation and equitable access for high quality learning opportunities in digital age classrooms. The potential benefits include an increase in student devices and of equal importance, training to address effective technology implementation. In addition to essential teacher technology embedded professional development, other expected outcomes, with designated funding, include increased student privacy awareness, expanded parent engagement with the use of digital tools and greater use of data driven personalized learning.

As history has shown, the role of schools, classrooms, teachers and administrators are ever changing. Twenty-first century classrooms are in a state of revolutionary transformation (U.S. Department of Education, 2014; Worthen & Patrick, 2015). In order to meet the demands of 21st century learning as highlighted in ESSA, NETP, CCSS, and the P21 Framework, there has been a paradigm shift in education having a direct impact on districts across the nation. Researchers, national organizations and policymakers aim to create effective frameworks that will guide and support funding as states and districts shift to personalized learning in order to ensure everywhere, all-the-time learning for all students. Technology allows for personalized learning models that open the door for students to take ownership and become empowered in their educational journey. Additionally, technological innovations provide unprecedented authentic learning experiences to students inside and outside of school. It is evident that educational stakeholders are beginning to collaborate in order to develop solutions to digital age concerns, in support of the vision of equitable and accessible high-quality world class learning for all students (U.S. Department of Education, 2016; Wegner, 2015; Worthen & Patrick, 2015). The time has come for school districts and stakeholders to take action together in order to develop instructional expectations, create responsible usage policies, secure funding and provide professional development to maximize the impact of technology on teaching and learning (U.S. Department of Education, 2016). It is the ethical responsibility to provide a device for every student in order to close the digital use divide and allow all learners to thrive as successful participants in a globally connected society.

References

Bosco, J. (2013). Rethinking acceptable use policies to enable digital learning: A guide for school districts. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.cosn.org/ConnectedLearning

Callaghan, B., Costa, J., Roberts, L., Andrews, K., & Dach, E. (2013). Learning and technology policy framework. Edmonton. Retrieved from https://education.alberta.ca/media/1046/learning-and-technology-policy-framework-web.pdf

Cook-Harvey, C. M., Darling-Hammond, L., Lam, L., Mercer, C., & Roc, M. (2016). Equity and ESSA: Leveraging educational opportunity through the every student succeeds act. Palo Alto. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/search/site?keyword=21st century

Crichton, S., Pegler, K., & White, D. (2012). Personal devices in public settings: Lessons learned from an iPod touch/iPad project. The Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 10(1), 23–31. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ969433.pdf

Evans, C. (2014). Universal design for learning. Columbia. Retrieved from http://www.hcpss.org/f/aboutus/bridge-to-excellence-udl.pdf

Gordon, D., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. H. (2014). Universal design for learning: theory and practice. Wakefield:MA: CAST Professional Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Universal-Design-Learning-Theory-Practice/dp/0989867404/

Greaves, T, Hayes, J, Wilson L, Gielniak, M, Peterson, R. (2010). The technology factor: Nine keys to student achievement and cost-effectiveness. Retrieved from https://www.k12blueprint.com/sites/default/files/Project-RED-Technolgy-Factor.pdf

Greaves, T. W., Hayes, J., Wilson, L., Gielniak, M., & Peterson, E. L. (2012). Revolutionizing education through technology. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://one-to-oneinstitute.org/images/books/ISTE_Book.pdf

Hutchison, A., & Woodward, L. (2014). A planning cycle for integrating digital technology into literacy instruction. The Reading Teacher, 67(6), 455–464. http://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.1225

Imbriale, R. (2013). Blended learning. Principal Leadership, 13(February), 30–34. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1006997

ISTE. (2016). ISTE Standards for students @2016.

King, J., South, J., & Stevens, K. (2016). Advancing educational technology in teacher preparation: Policy brief. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://tech.ed.gov/files/2016/12/Ed-Tech-in-Teacher-Preparation-Brief.pdf

Lambert, J., & Cuper, P. (2008). Multimedia technologies and familiar spaces: 21st-Century teaching for 21st-Century learners. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 8, 264–276.

Mesecar, D. (2015). Early education programs in the every student succeeds act. American Action Forum, (December). Retrieved from https://www.americanactionforum.org/contact-us/

Moore, A. J., Gillett, M. R., & Steele, M. D. (2014). Fostering student engagement with the flip. Mathematics Teacher, 107(6), 420–425. http://doi.org/10.5951/mathteacher.107.6.0420

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2017). Common core state standards. Washington, DC, United States.

Rose, R. (2014). Access and equity for all learners in blended and online education. International Association for K-12 Online Learning, (October), 1–26. Retrieved from http://www.inacol.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/iNACOL-Access-and-Equity-for-All-Learners-in-Blended-and-Online-Education-Oct2014.pdf

Rose, R. M., & Blomeyer, R. L. (2007). Access and equity in online classes and virtual schools. Online, 1–19. Retrieved from http://www.inacol.org/research/docs/NACOL_EquityAccess.pdf

Schools, A. P. (2015). iAndover 1:1 learning initiative. Andover. Retrieved from http://www.aps1.net/

Schwieger, A., & Rivereo, V. (2016). Digital equity: Supporting students & families in out-of-school learning. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.cosn.org/sites/default/files/pdf/CoSN-EQUITY-toolkit-10FEBvr_0.pdf?sid=13181

Sykora, C. (2014). Plan a successful 1 : 1 technology initiative. Retrieved from https://www.iste.org/explore/articleDetail?articleid=36

U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology. (2010). Transforming American Education: Learning powered by technology. E-Learning and Digital Media, 8(2), 102–105. http://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2011.8.2.102

U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology. (2014). Future ready schools: Building technology infrastructure for learning. Retrieved from http://tech.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Future-Ready-Schools-Building-Technology-Infrastructure-for-Learning-....pdf

U.S. Dept. of Education Office of Educational Technology. (2016). Future ready learning: Reimagining the role of technology in education. Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://tech.ed.gov/files/2015/12/NETP16.pdf

Wolfe, L., & Pozo-Olamo, J. (2014). ISTE and the verizon foundation launch free mobile learning academy for educators. Retrieved from Verizon Mobile Learning Academy

Worthen, M., & Patrick, S. (2015). The iNACOL state policy frameworks 2015:5 critical issues to transform K-12 education. Vienna:VA. Retrieved from http://www.inacol.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/iNACOL-State-Policy-Frameworks-2015.pdf