The Education Technology Value Chain: Implications and Policy Options

- By Glenn Pierce, Paul Cleary

- 08/11/16

Implementing, maintaining and managing computer technology has been extremely difficult for most K-12 educational systems. The sometimes-impressive facade of computers gracing desktops in many schools obscures a more sobering reality that educational technology is often so unreliable its utility to students and teachers is negated. Consequently, opportunities for significant productivity gains from educational technology including pedagogical advances, closing the achievement gap and facilitating K-12 reforms have gone unrealized.

Nevertheless, education technology appears poised to make major contributions to K-12 education. Increasingly, research finds that technology can make a positive impact on educational performance (for example, see the meta-analytical studies by Cheung & Slavin; 2012, 2013, Zheng et. al., 2016). Moreover, a growing body of evidence now suggests that when systematically implemented, educational technology can support a wide range of educational innovations, including flipped classrooms, peer-to-peer teaching, and customized learning.

The Education Technology Challenge

However, the prolonged implementation phase of K-12 educational technology is not exceptional when compared with other transformative technologies, such as steam power, electricity and earlier generations of computing. Steam power took approximately 80 years from Watts's first steam engine to realize significant gains in manufacturing productivity (Crafts, 2004). In a similar manner, electric power took approximately 40 years before electric dynamo technology yielded dramatic increases in manufacturing productivity (David, 1991). More recently, the failure to identify productivity gains from the massive investments in computing technology by American businesses was labeled a as "productivity paradox," a perception that changed dramatically after the mid 1990s.

Why did it take so long to realize productivity gains from these different transformative technologies?

David (1991) concluded that lags in productivity were owing to:

- The initial unprofitability of replacing existing functioning technology;

- The need to identify and integrate complementary technical components; and

- The need to integrate the new technology into organizational processes (David, 1991).

Today, challenges to the successful introduction of educational technology into the K-12 system are similar to those faced by previous transformative technologies because success requires implementation of an entire system of technological and organizational innovation, not just a single stand-alone invention.

Given the significant opportunities offered by educational technology, a major policy question facing the United States today is how to optimize its potential in the quickest and fairest way possible for the entire K-12 system. To examine this challenge, we have adopted a technology value chain framework. The framework is designed to:

- Identify bottlenecks in educational technology implementation initiatives that have impeded its adoption in the past; and

- Assess the readiness of the K-12 system to integrate these technologies into the nation's schools to produce significant benefits for students, schools and society.

The Education Technology Value Chain

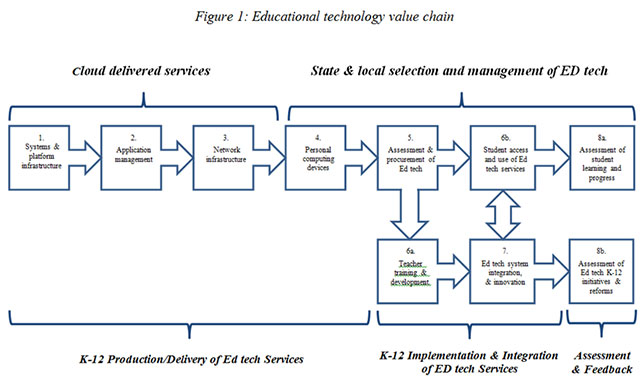

The value chain model developed for this analysis (see fig. 1) assesses the technological, organizational and human capital components of the K-12 educational technology system. The framework presented here takes an institutional level perspective of the provision of educational technology to K-12 schools and we examine how technological, organizational, administrative and even demographic trends can affect the delivery of educational technology services to K-12 schools.

Components 1 through 4 focus the potential of today's rapidly evolving cloud technology infrastructure that can support the centralized delivery of educational technology services. Components 5 through 7 concern the adoption and integration of education technologies into K-12 organizations. Component 5 focuses on the educational technology assessment and procurement process; Component 6 concerns the adoption of educational technology by students and teachers, and component 7 focuses on the integration of educational technology into K-12 curricula and initiatives. Finally, component 8 focuses the assessment and feedback systems necessary to evaluate the impact of K-12 education technology (Manzi, 2012).

Assessing the K-12 Education Technology Value Chain

Components 1 through 4: Information Technology Infrastructure: Today, there is a growing consensus among information technologists that Cloud computing can support K-12 educational technology, and at lower costs (Marston et al. 2011). Cloud computing services provide on-demand access to shared computing resources software application services. Economies of scale delivered by cloud computing services enable them to provide expert technical talent that is generally unavailable to smaller organizations like K-12 school systems. In addition, cloud services, along with appropriate software and service licensing agreements, provide organizations with much greater flexibility to scale-up or scale-down application services based on customer demand and experience.

Cloud delivered educational applications can also significantly reduce end-user (i.e., students and teachers) costs associated with learning education technology applications. Because Cloud services can provide educational technology applications on an anytime/anyplace/anydevice basis, teachers and students gain the flexibility, time and access needed to become proficient with educational technology.

Cloud service models depend on the ability of individuals to access the Internet. National surveys find continued gaps in access to the Internet by geographic location, ethnicity, race and socioeconomic status (November; NTIA, 2011, February). Various federal initiatives aimed at underserved groups have had varying degrees of success to date (November; NTIA, 2011, February), and more recently, the ConnectED initiative was established to bring Internet connectivity and high-speed wireless access to virtually all K-12 schools (NTIA, July 1, 2013).

In addition to providing technology applications, access to reliable end user computing devices (Component 4) has posed a significant impediment to implementing educational technology. Dramatic decreases in the cost of end-user computers along with web browser technology that provides a common interface across different computers devices has greatly reduced the financial burden of this component (Credit Suisse data). Moreover, Gartner (May, 2016) projects that by 2020 at least 70 percent of K-12 school districts will be engaged in some form of a 1-to-1 computing initiative for students, whether focused on particular grade levels or districtwide.

Component 5: Educational Technology Assessment and Procurement: Negotiating education technology licensing and service agreements requires flexibility to field test, adopt and, if desired, discontinue particular applications or services. To navigate this complex landscape market influence matters. Larger negotiating groups are better positioned to negotiate cost-effective, flexible agreements from educational technology vendors. Fortunately, given the existing state and local level governance structure of K-12 systems, comprehensive educational technology assessment and acquisition processes can be integrated into existing planning systems and organizations. From a policy perspective, this will help ensure that state education standards and procurement procedures are maintained and that all relevant stakeholders have ongoing input into the selection and acquisition of educational technology applications.

Gartner Group (December, 2015) estimated that IT spending as a percent of revenue from all educational institutions (i.e., higher education, other post-secondary schools and K-12 systems) rose 5.2 percent of operating expenses in 2014 to 5.6 percent in 2015. Nevertheless, funding constraints, in all probability, continue to be a major factor slowing the adoption of education technology into K-12 systems. Within the education marketplace, K-12 systems are likely to spend less on education technology then there higher education counterparts. In addition, constrained local school budgets, combined with often restrictive budgeting processes in many K-12 systems, means that school districts are often unable to look forward to increased funding from their own communities for educational technology initiatives (even at good prices). As a result, K-12 systems operate with fewer resources devoted to IT than their higher education counterparts (and many other information-intensive organizations).

Component 6: Teacher Training, Educational Applications and Student Achievement: The successful adoption of education technology also depends on teachers learning and integrating these technologies into their curriculum. Fortunately, a national survey of teachers, found that most teachers already use computer technology on a regular basis (PBS Learning Media, 2012, January). In addition, as technology-savvy younger teachers increasingly replace retiring "Baby Boom" teachers, training will become less problematic. Finally, cloud applications will enable teachers and students alike to spend more of their time using applications rather than trying to access limited computing resources. Given changing teacher demographics, existing teachers' experience with technology and growing accessibility of Cloud delivered educational applications training is likely to become less of a constraint to implementing educational technology.

With a clearer view of educational benefits and the development of common curriculum standards, private investors are increasing their commitment to develop education technology. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Google have provided support for application developers seeking to address historically difficult problems in math and reading literacy products (Gates Foundation, 2014). In terms of private sector contributions, President Barack Obama announced commitments totaling $750 million from several technology companies to help low-income students in K-12 public schools gain access to the Internet and educational tools (Cheng, 2014).

Component 7: Curriculum Development and Education Reform: Research has found that that when teachers were encouraged and supported in using technology in their classrooms they changed the way they taught their classes because computers became "a catalyst for supporting 21st century skills" (Levin & Schrum, 2013). More generally, evidence is growing that education technology applications can support new approaches to education, including flipped classrooms, collaborative teams and peer-to-peer learning environments (Mitra, S. and Dangwal, R., 2010 and Staker & Horn, 2012).

Equally important, the centralized delivery of Cloud services can greatly assist in reducing the technology resource gap that confronts economically disadvantaged communities because there is less need to build local infrastructure and IT support. In addition, cloud-delivered collaboration applications can facilitate communities of best-practices education and technology forums that engage stakeholders across K-12 systems.

Component 8: Assessment and Evaluation of Outcomes: Transformative technologies typically have multiple outcomes that need ongoing assessment to optimize their performance. Fortuitously, strategies for assessing organizational performance are developing in many different fields. The developments hold the potential to provide individualized feedback and more customized education for learners (for example, Taylor, 2013, July 17, Financial Times). Such developments in what we now term "big data" analytics should enable schools to customize and change their programs and initiatives to better meet the needs of their students.

The Potential of Educational Technology and the K-12 System

Examination of the educational technology value chain indicates the U.S. is well positioned to consider implementing educational services on a more comprehensive basis because many of the components of an educational value chain are already in place or potentially available.

Societal returns on such investments can be great. Immediate benefits include increased achievement and competency of K-12 students in science and mathematics (STEM) subject areas and in reading and writing. In addition, Cloud services can also help reduce the achievement gap and close the digital divide. Over the longer term, new workforce entrants with 21st skills will help the nation maintain its position in the global marketplace.

Although not guaranteed, cloud-delivered technologies could provide potentially powerful levers to support K-12 innovations, including:

- Customizing education to meet the diverse learning styles of students;

- Supporting the development of new K-12 education models not possible in the past;

- Supporting national education goals; and

- Developing Cloud facilitated communities of best educational practices.

However, implementation of education technology faces major challenges.

First, current investment in K-12 information technology is substantially lower compared to comparable institutions and organizations, and local school districts often face limited prospects for additional funding for technology. Funding constraints combined with localized planning processes combine to mean that the most education technology initiatives are implemented on a piece meal basis, leaving such initiatives to fail or underperform owing to insufficient support and/or shortfalls in other parts of the value chain. As a consequence, many educational initiatives underperform.

Federal or state-level funding significantly could reduce current K-12 technology supply constraints and enable educators to focus on the selection and implementation of educational technology on a more comprehensive basis rather than scrambling to fund initiatives on a piecemeal basis. External funding would support more comprehensive educational technology initiatives that would engage entire school systems where all components of the value chain could be implemented in a coordinated manner. This would also encourage more comprehensive and inclusive planning processes.

To test this proposition, we propose the federal government, collaborating with states, technology providers and foundations, fund a set of comprehensive educational technology field tests. Appropriately scaled field studies would allow us to assess how well cloud education technology services can most optimally combine the advantages of economies of scale with the ability of local K-12 systems to control and customize educational technology to meet the needs of their students, schools and society.

References

Cheng, R. (2014, February, 4). Apple, Microsoft join carriers in $750 M pledge to education. CNET.com. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://news.cnet.com/8301-13579_3-57618291-37/apple-microsoft-joincarriers-in-$750m-pledge-to-education/

Cheung, A., & Slavin, R. (2013). The effectiveness of educational technology applications for enhancing mathematics achievement in K-12 classrooms: a meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 9, 88–113.

Cheung, A., & Slavin, R. (2012). How features of educational technology applications affect student reading outcomes. A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 7, 198–215.

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). (2012, January 23). Learning Media Release, 1–2

Crafts, N. (2004). Steam as a general purpose technology: a growth accounting perspective. The Economic Journal, 114(495), 338–351.

David, P. (1991). Computer and dynamo: The modern productivity paradox in a not-too-distant mirror. In Technology and productivity: The challenge for economic policy (pp. 315–348). Paris: OECD Technology/Economy Programme.

Gartner Group (2015, December). IT Key Metrics Data 2016: Key Industry Measures: Education Analysis: Multiyear, Analysts: Hall, L., Stegman, E., Futela, S., Gupta, D.

Gartner Group (2016, May). Avoid Sinkholes on the Road to 1:1 Computing in K-12 Education. Analyst, Calhoun, K.

Gates Foundation (2014). Literacy Courseware Challenge Request for Proposal, Retrieved March 18, 2014 from http://www.gatesfoundation.org/How-We-Work/General-Information/Grant-Opportunities/Literary-Courseware-Challenge-RFP#GoaloftheLiteracyCoursewareChallenge

Levin, B., & Schrum, L. (2013). Using systems thinking to leverage technology for school improvement: lessons learned from award-winning secondary school district. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(1), 29–51.

Manzi, J. (2012). Uncontrolled, the Surprising Payoff of Trail-and Error for Business, Politics and Society. New York: NY. Basic Books.

Marston, Sean, et al., (2011). Cloud computing – The business perspective, Decision Support Systems, September 51, pp. 176–189

Mitra, S., & Dangwal, R. (2010). Limits to self-organizing systems of learning the Kalikuppam experiment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(5), 672–688.

NTIA (July, 1 2013). Connecting America's Schools to Next-Generation Broadband. Retrieved March 18,2014,

PBS Learning Media (January 23, 2012). National PBS Survey Finds Teachers Want More Access to Classroom Tech. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://www.pbs.org/about/news/archive/2012/teachersurvey-fetc/.

Staker, Heather & Horn, Michael B. (2012, May). "Classifying K-12 Blended Learning", Innosight Institute Inc.

Taylor, Paul (2013, July 17). "Technology is the key to teaching future skills", Financial Times, 1–2

U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications & Information Administration (NTIA). (2011, February). Expanding Internet Usage: The Digital Nation, 1–60

U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications & Information Administration (NTIA). (2011, November). Exploring the Digital Nation: Computer & Internet Use at Home, 1–72,

Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C. and Chang C., (2016) Learning in one-to-one laptop environments: a meta-analysis and research synthesis, Review of Educational Research, Available online DOI: 10.3102/0034654316628645.

Acknowledgment. We would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Grady for her insights on the integration of educational technology into K-12 curricula and organizational systems

Parts of this paper are excerpted from, Pierce, G. and Cleary, P. (2016) "The K-12 Education Technology Value Chain: Apps for Kids, Tools for Teachers and Levers for Reform" (with Paul Cleary) Education and Information Technologies, 21:863–880.