K–12 Cyber Incidents Have Been Increasing in 2017

The creator of a national K–12 Cyber Incident Map warns that schools should act now, not later, to bolster their security.

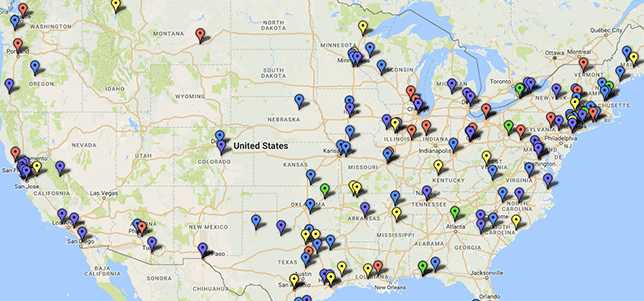

Ed Tech Strategies' K–12 Cyber Incident Map. Courtesy of Doug Levin.

The founder and operator of a K–12 Cyber Incident Map is sharing some lessons he has learned after collecting data over the past 17 months on cyber incidents at United States schools.

Doug Levin, president of Ed Tech Strategies, a Virginia-based research and counsel consultancy, says that as K–12 schools increase their use and reliance on digital tools and services, the number of cyber incidents has also been on the rise — exponentially so.

Since Jan. 1, 2016, 141 U.S. K–12 schools and districts experienced one or more publicly disclosed cyber incidents. Sixty-seven incidents were reported during 2016, and 74 have been reported during the first five months of 2017. If the pace continues at the current rate, that will represent a more than 100 percent increase in 2017, compared to last year.

“Incidents and disruptions have been on the rise,” Levin said in an interview. “We have had more incidents in 2017 than all of 2016. We’ve seen more than double the number of incidents in schools.”

Levin attributed this rise to a few different factors: more awareness of nefarious cyber activities; more schools using more hackable technologies; more schools going 1-to-1 and relying on digital tools; and bad actors who continue to look for soft targets, such as students and school staff.

“They’re looking for vulnerable targets,” Levin said. “My sense is that as schools increase reliance on technology, [cybercriminals] are finding that schools are softer targets.”

Levin has been tracking the publicly disclosed K–12 incidents on a color-coded map on his website, edtechstrategies.com. His sources include media reports, DataBreaches.net and the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse.

Some cyber incidents at U.S. K–12 schools that Levin has tracked include phishing attacks that procure personal data; ransomware attacks; denial-of-service attacks; “other unauthorized disclosures, breaches or hacks” that disclose personal information; and other cyber incidents that have caused school disruptions or closures.

“In many cases, they’re not very sophisticated at all,” Levin said. “They don’t need to be successful very often. They just need one or two people out of millions to respond. Then they can get paid. They can get their money.”

In a post published this week on the newly revamped Ferpa Sherpa education privacy site, Levin argues that not only have schools been “experiencing an increasing number of cyber incidents,” but “the range of cyber threats affecting schools appears to be diverse and shifting over time.”

Furthermore, students are not the only ones whose personal information is in jeopardy. “Personal data about school system employees is being targeted and also is at risk,” Levin states.

“We have too often confounded the issues of privacy and security in policymaking about technology in schools,” Levin said. “We have focused more on the types of data schools and their vendors are collecting and with whom it can be shared and less on the legal, technical and practical steps we expect schools and vendors to take to ensure that these data remain only accessible to authorized parties. The former speaks to privacy issues; the latter to security issues. Both are important, but based on my research I would argue that more attention is needed on issues of IT-related security.”

Levin wants to dispel the notion that intrusions and hacks are always done by external actors. Based on the statistics, a significant proportion of incidents are done by educators themselves, school staff and students.

Students are “hacking their own schools to improve their grade,” he said. “They’re changing info on the website, or teachers’ websites. They’re sending sordid emails to everyone in the school community. In some cases, it’s just kids being kids.”

Levin notes that a significant number of K–12 student who were caught hacking into their schools were charged as criminals under state and federal law — and were likely to go to prison if convicted.

“We certainly have a question as to whether the best way to sanction or penalize these students is the existing legal framework — that may be too harsh,” he said.

Levin has built his K–12 map based on publicly reported incidents. However, there are probably many more incidents that have not been publicized, he said. Schools may not want to share the bad publicity, or admit that there are weaknesses in their electronic security systems.

Still, there are concrete steps schools can take to improve their security, such as:

- Use special software or hardware to protect data;

- Create better password and authorization policies;

- Use secondary authentication methods;

- Train school staff, particularly about phishing and downloading of unfamiliar files; and

- Hire more staff with IT security expertise.

Schools should not wait to bolster their security, Levin warned. “Unless they take cybersecurity more seriously, there will be legal action,” he said. “We’re starting to see lawsuits filed and potential legal action being brought by those who are affected by these incidents.”

So the time to act is now, Levin suggested, and “it’s important to think more broadly than just about the students.”