How to Use Games to Juice up Science Lessons

The use of gaming for student-centered learning eliminates constraints, increases engagement, boosts collaboration and empowers students to find answers through deep and rich experiences.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 05/23/18

Tammie Schrader was never a gamer. But one day in a middle school science class she assigned a game on plant cells to her students to help them review the concepts. One student, a "really bright kid" who would typically "pick and choose" what he would work on, came into class the next day and handed her a thumb drive. On it was a version of a Nintendo Mario game intended to do the same thing. When a learner wanted Mario to jump up to grab a coin, he or she would first have to answer a plant question. If the answer was right, the student would get the coin; if not, he or she "would fall through the tube." Schrader was impressed enough with the student's hack that she put it on her interactive whiteboard to share with the class. All day long, she found, "kids wanted to play this game." Soon, students from other classes were coming in before and after class and during lunch and asking if they could try it out too.

It didn't take long for Schrader to call her principal in to see the results. The message: "OK, so I'm not meeting the needs of my kids. Even though I don't use games, they do, and I think we need to start leveraging it."

Since then she has become a big fan. By letting students interact with the information through gaming, she has discovered, that's where the learning happens. "When you present ideas to kids, it's when they talk through it that they begin to understand it."

Now Schrader serves as the science and computer science coordinator for NorthEast Washington Education Service District 101 in Washington state, where she helps educators implement Next Generation Science Standards by working with districts to develop and deliver professional development. And she introduces gaming into science classes wherever she sees a fit.

The idea of using games to facilitate student-centered learning doesn't eliminate "good teaching," said Meenoo Rami, author, trainer and teacher and, currently, manager for Minecraft: Education Edition. "The content doesn't go away. It's more about meeting the students where they are, taking their passion and turning it into an opportunity for learning."

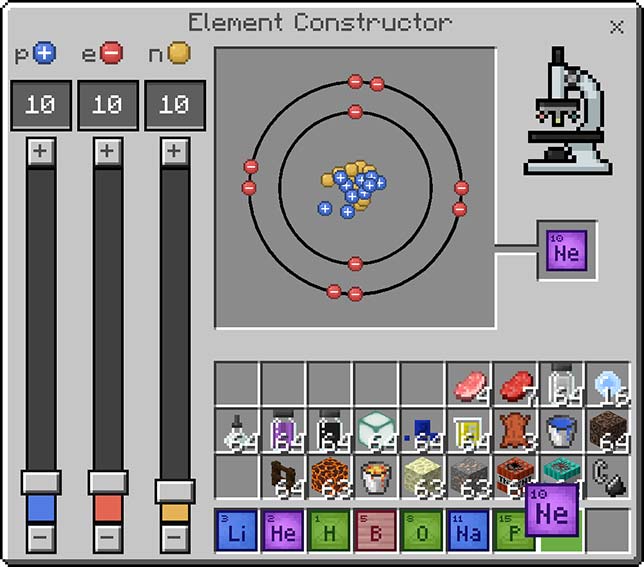

Minecraft, of course, is the online platform that enables users to construct environments "block by block" and populate them with animals and people, real and imaginary. In 2016 Rami's employer, Microsoft, acquired Minecraft: Education Edition, a special edition of the open world, and began building up its functionality for classroom use. Most recently, the company released Minecraft Chemistry, a resource pack for helping students learn chemistry within the game. Resources for that include new lessons and activities, a teacher lab book, a downloadable world and community support.

Hitting Student-Centered Learning Where It Counts

Both educators believe that gaming can hit the target in student-centered learning better in several ways than many other instructional techniques for science, by offering a better way to simulate real life, promoting persistence and prompting authentic collaboration.

Gaming eliminates constraints. That might be limitations related to time or those related to concepts. If the unit is covering the topic of recessive and dominant genes, as Schrader's was, nobody has the time to "grow generation after generation of plants in order to do that study, because it takes time for plants to grow," Schrader explained. "But if I can find a game that matches that need, then it helps model that for kids so they understand it."

Likewise, for a unit that teaches about the solar system, students could draw or build physical models, "but they just don't do it justice," noted Schrader. The right games, on the other hand, can allow the learners to "go in and change the tilts of planets, move the distance from the sun and change the revolution and the location and can see what that does to the environments of the planets."

The best game developers have mastered persistence. They understand how to create games with that "sweet spot," said Schrader, where kids will continue playing through the confusion." That's not true for science labs, she added. "Sometimes when I was teaching, I'd give kids experiences. If they didn't get it the first time, they'd go, 'Mrs. Schrader I can't do it.' With games, they will try and try and try. They will stay with it long enough to figure it out. It's amazing."

Rami agrees. "Resilience, that ability to overcome a bump in the road to learning, that ability to start over, to try and try again, that is naturally cultivated in a platform like Minecraft."

Playing educational games encourages collaborative problem-solving. Crazy Plant Shop from Filament Learning, a game that allows students to "breed wacky plants" in order to learn about trait inheritance and plant genetics, demonstrated this point to Schrader. In the game, customers come into the shop to order different kinds of plants, and students need to cross-breed their specimens correctly to achieve the right results. "Kids are looking at each other, and they're competing a little bit — and not in a bad way," she observed. If one student had a cactus with a rainbow, others would try to emulate the effect and then turn to each other for help on how to do it. They all wanted the cactus with the rainbow and would start working together around a common goal. "Not only are they talking across the classroom, they're collaborating. They want to know how it works. They're into their own thing, but they're also wondering what [other] people are doing."

The importance of game-based collaboration shouldn't be minimized, Rami emphasized. "By working together in groups, students are not only mastering content and skills, like reading to understand, but they're also learning how to talk to one another about their ideas, how to compromise, how to build a plan before starting to build something together, how to negotiate when there is a disagreement," she said. "These so-called 'soft skills' or 'future-ready skills' of communication, creativity, problem solving and collaboration really come into play when students have a chance to make meaning with their peers."

Even the most reticent students will participate. Schrader has seen proof among even the most traumatized students that games can engage on a level nothing else will. The experience of one student, in particular, stands out. He was severely autistic and couldn't sit next to other children without disruption. "But he loved to game," she said. And he was really good at it, which the other kids noticed. When they sought his help and it was something "that mattered to him," he'd work with others. When he'd get overwhelmed, he'd return to his gaming. "What I loved was [that] it was a way for him to collaborate authentically. This kid got to be a rock star."

Games have built-in assessments. While "leveling up" may be the ultimate form of testing for gamers, practically speaking, the best games also facilitate other more traditional forms of assessment. As an example, Minecraft's education version allows students to export their construction results into a presentation or a report or even a 3D form. These props can serve as a backdrop for their self-reflections, explained Rami, "not just on the build, but on the process they went through — what decisions they made, what materials they chose, what specific systems make the homes sustainable or not, [and that's] really where the learning comes in." During her years as a teacher, she said, "The process in their thinking about the work they were doing was always more important to me than the shiny product at the end."

Another Tool in the Toolbox

Schrader once heard a trainer in professional development say something that has always stuck with her: "You don't get to choose what motivates the children in your classroom." She has found that games provide a "key to unlock" what's needed in order to help them learn.

Rami concurred. How games are used to create "a learning experience from beginning, middle, to the end is still in the hands of the teacher." But where it makes sense, she added, educators "should consider its use because your students obviously love it and are engaged by it. The teacher remains the expert of pedagogy. This is just another tool in their toolbox."

Gaming to Fill in Gaps

Texas' Ector County Independent School District is in its second year of using Stride, an adaptive learning tool that integrates games, from Fuel Education (owned by K12 Inc.). According to Lisa Wills, executive director of Curriculum & Instruction, the program in her district specifically addresses K-8 in math and English language arts and is used as a supplement for "tier two" individualized instruction — students who "need a little bit more intervention throughout the day."

The kids work on problems assigned by teachers to address "gaps they might have." After they've worked for a certain period, earning coins along the way, they're given "brain breaks" to play games. If the program suspects they're guessing just to get to the gaming, it warns them that they'll lose coins. If they continue doing so, the points disappear (though they can be returned by the teacher if she believes they've learned a lesson).

Where the application is finding its biggest growth in the 32,000-student district is among its special education students. As Wills explained, the benefits are the same: keeping them motivated, helping them fill in learning gaps and, most importantly, allowing them to "feel like they're like the other kids. They feel included — doing what the other students get to do."

Stride is available in English and Spanish and addresses learning standards for the Common Core, as well as multiple states.