Ability to Compare Learning Outcomes Becomes a Global Goal

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 01/29/19

Even as the Common Core is faltering in the United States as a way to compare student success across state borders, UNESCO is making a plea for standardized ways to measure learning outcomes around the world. A December report from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) examined progress on Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), a global effort to bring "inclusive and equitable quality education" and lifelong learning opportunities to every part of the globe.

According to current data from the UIS, more than six in 10 young people (617 million worldwide) can't read a simple sentence or handle a basic math calculation. While a third of these children are out of school, two-thirds are in school, "sitting in classrooms, waiting for schools to deliver the quality education they have been promised," said Silvia Montoya, UIS director, in a statement. "That promise has been broken far too often."

SDG 4 is one of 17 goals adopted by United Nations member states as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Education is at the heart of all of the SDG goals, Montoya's organization suggested, since learning has an impact on reducing poverty (goal 1), tackling gender discrimination (goal 5) and building peaceful societies (goal 16). However, the SDG includes several targets specifically related to education, including four pertaining to learning outcomes. As an example, the first target, 4.1, measures the share of children and young people at three points in their lives — in grades 2 or 3, at the end of their primary education and at the lower end of lower secondary education — who have achieved at least a minimum proficiency in reading and math.

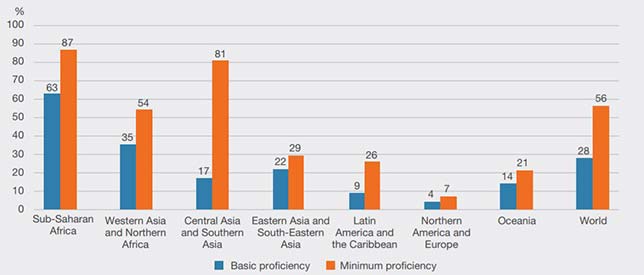

Tracking such data allows for "comparability of national statistics over time," which deserves "more attention," the report, "SDG 4 Data Digest: Data to Nurture Learning," noted. For example, in the latest reporting, while seven percent of students failed to reach minimum proficiency in reading for North America and Europe, the number was 12 times higher for in Sub-Saharan Africa and 11 times greater in Central and Southern Asia.

The proportion of students not reaching basic and minimum proficiency levels in reading. The minimum level is higher than the basic level of proficiency. Therefore, more students don't achieve the minimum proficiency level than do achieve the basic level. Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

The challenge in doing this work is that countries and regions of the world have varying levels of complexity for the items being used to measure whether students are meeting the proficiency benchmarks in different grades. "Some countries apply more stringent items to measure certain proficiency levels than others," the authors stated, adding, "This obviously makes it more difficult to reach a global consensus around proficiency benchmarks." Likewise, the comparisons are tricky because formal years of school vary; while students in some countries are done with primary school in the fourth grade, others go until the sixth grade or even later.

Resolving these obstacles will take "several years," the report pointed out. But in the meantime, to keep the topic front and center, the UIS will use an "interim reporting strategy," which uses available data.

The digest also highlighted positive progress and offered tools and methodologies to help countries choose the types of assessments that would meet their needs.

The report made a strong case for investing in international or regional assessments, which can cost each country about $500,000 every four years. That may seem "like a major expense for a smaller economy," the authors wrote, "however, it is minor when set against the overall cost of providing schooling, and the even greater cost of a lack of education." And compiling a "solid" source of data on learning to understand whether approaches are working or reforms are needed could boost the efficiency of education spending by five percent, the report observed, "saving $30 million each year in the average country and paying for the cost assessments hundreds of times over."

The full report is openly available on the UIS website.

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.