Technology Literacy as a Catalyst for Systemic Change

- By Dennis O. Harper, Rebecca F. Kemper

- 09/20/21

The K–12 education system

needs to change.

This sentence has been uttered for centuries, and millions of

educators and billions of dollars have attempted to make this change.

John Dewey, Jean Piaget, Maria Montessori, Seymour Papert, Jonathan

Kozel, and many others spent their lives developing proven models of

teaching and learning. National efforts such as “A Nation at Risk”

(United States, 1983), Technology Innovation Challenge Grants (U.S.

Department of Education, 1995), and “No Child Left Behind”

(United States, 2001) are just three examples of recent efforts to

systematically change schools. So why haven’t these efforts

resulted in significant change? Why have we read every year for the

past century that “the K–12 education system is in crisis?”

This article will argue that

three factors are now (2021) different and can result not only in

meaningful educational reform but also in overall systemic change in

systems beyond education. The article then will propose that

technology literacy is the catalyst to take these new factors into

account and create overall global systemic change. This article will

further provide five Suggested Solutions that could be implemented by K–12 schools that can address both technology literacy and systemic

change.

Zachary

Stein (2019) in his book "Education in a Time Between Worlds”

summarizes what current education system reform should entail and why

it is key to reforming systems beyond education.

"Those

preoccupied with 'fixing' the existing system of schools do not stop

to ask questions about what schools are for, who they serve, and what

kind of civilization they perpetuate. As I have been discussing, our

civilization is in transition. Across the planet major

transformations are underway -- in world system and biosphere -- that

will decenter the core, reallocate resources, and recalibrate values,

the economy, and nature itself. This is the task of education today:

to confront the almost unimaginable design challenge of building an

educational system that provides for the re-creation of civilization

during a world system transition. This challenge brings us

face-to-face the importance of education for humanity and the basic

questions that structure education as a human endeavor."

This

article is more than reforming the K–12 education system. It is about

changing all systems. We will present a case for how to meet the

challenge identified by Stein to “rebuild an educational system

that provides for the re-creation of civilization during world system

transition.” We will suggest that achieving this rebuild is now

possible for three reasons: urgency, technology, and youth infusion.

We then argue that K–12 technology literacy is a key catalyst for

achieving systemic

change.

The article will conclude with five examples of ways schools begin

rebuilding the education system to achieve the above goals.

Defining

Technology Literacy, Catalyst, and Systemic Change

Prior to building a case for K–12 technology

literacy as a key

catalyst for

systemic change,

we need to clarify our definitions of the three major terms in this

article’s title.

K–12 Technology Literacy

— What does it mean for a K–12 student to be technology literate?

What should a high school student need to know upon graduation from

high school? To be literate in any subject area is always a moving

target. As time passes more history happens, more literature is

written, more science is discovered, etc. Technology literacy is

perhaps the most fluid of all literacies. The current pandemic has

shown that first graders have had to master distance learning apps

and cloud-based environments, skills that heretofore were not

considered necessary.

The International Society for

Technology in Education (ISTE) has addressed technology literacy for

the past 20 years by developing the comprehensive ISTE Standards for

Students (ISTE, 2016). These standards divide technology literacy

into seven key components.

|

Seven

Components of the ISTE Technology Standards for K–12 Students

|

|

1

- Empowered Learner

|

Students

leverage technology to take an active role in choosing, achieving,

and demonstrating competency in their learning goals, informed by

the learning sciences.

|

|

2

- Digital Citizen

|

Students

recognize the rights, responsibilities and opportunities of

living, learning and working in an interconnected digital world,

and they act and model in ways that are safe, legal and ethical.

|

|

3-

Knowledge Constructor

|

Students

critically curate a variety of resources using digital tools to

construct knowledge, produce creative artifacts and make

meaningful learning experiences for themselves and others.

|

|

4

- Innovative Designer

|

Students use a variety of technologies within a design process to identify and solve problems by creating new, useful or imaginative solutions.

|

|

5

- Computational Thinker

|

Students

develop and employ strategies for understanding and solving

problems in ways that leverage the power of technological methods

to develop and test solutions.

|

|

6

- Creative Communicator

|

Students

communicate clearly and express themselves creatively for a

variety of purposes using the platforms, tools, styles, formats

and digital media appropriate to their goals.

|

|

7

- Global Collaborator

|

Students

use digital tools to broaden their perspectives and enrich their

learning by collaborating with others and working effectively in

teams locally and globally.

|

There are hundreds of attempts

to define technology literacy, but, for our purposes, we use the

following definition because of its close alignment to the ISTE

Technology Standards for K–12 Students:

Technology

Literacy —

“Is

a term used to describe an individual’s ability to assess, acquire

and communicate information in a fully digital environment. In

practice, students who possess technology literacy are able to easily

utilize a variety of digital devices (e.g., computers, smartphones,

tablets) and interfaces (e.g., e-mail, internet, social media, cloud

computing) to communicate, troubleshoot and problem solve in both

academic and non-academic surroundings” (Top Hat, 2021).

Catalyst

— “A person

or thing that precipitates an event or change or something

that causes activity, an event, or change and usually, these events

and changes are big.” (Dictionary.com) In this article, Technology

Literacy is the catalyst and the change is systemic change.

Systemic Change

— “Put

simply, systemic change occurs when change reaches all or most parts

of a system, thus affecting the general behavior of the entire

system.” (Connolly, 2017)

Forum

for the Future, in May of 2019, convened over 40 senior leaders

across philanthropic, corporate and investment communities to share

ideas on how to activate systemic change (Uren 2019). In the below

table are nine strategies that came out of this forum:

|

Nine

Key Strategies to Create Systemic Change

|

|

1 -

Create a robust case for change

|

2 -

Make information accessible

|

|

3 -

Create collaborations

|

4 &

5 - Create disruptive innovations and routes for them to scale

|

|

6 -

Create the right incentives, business models and financing

|

7 -

Develop policies that facilitate and reinforce systemic change

|

|

8 -

Shift culture, mindsets and behaviors

|

9 -

Develop rules, measures and standards for the ‘new normal’

|

Achieving

each of these nine strategies for systemic change will require

technology literacy.

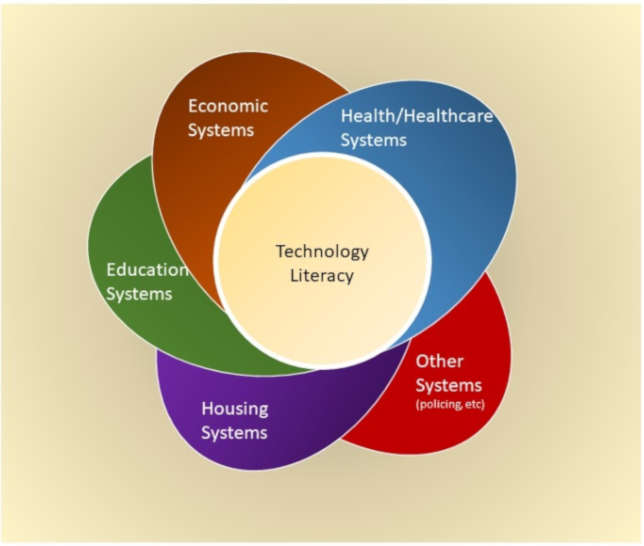

The

following diagram illustrates how these three definitions relate to

each other and show how K–12 Technology Literacy is the key catalyst

for system change.

Making

the Case

Achieving the ISTE Standards

for Students and realizing our definition of technology literacy has

had limited success. If our premise hinges on K–12 students being

technologically literate in order to address and achieve systemic

change, then we must briefly recognize the following major obstacles

and roadblocks.

-

Incurring a Cost for

Innovation: New

programs, training, technology, research, etc. require additional

funding. To move forward, schools need to procure additional funding

and/or cut existing programs. Both these options are difficult to

implement so schools decide that change is not worth the effort.

-

Technology is Considered

Tangential: Although

there is a T in STEM, and computer science is certainly now a major

science in STEM’s S component, schools still consider technology

literacy as defined above to be outside the traditional core

Language Arts, Math, Science, and Social Studies curricula. Related

to this is that there is no required technology literacy test.

Schools are hesitant to implement something if it doesn’t increase

test scores. Of course testing technology literacy as it is defined

above would be almost impossible and probably a bad idea.

-

Time Intensive:

Teaching and learning are more complex in terms of both singular

subject material and technological change. Teachers are already

overburdened with careers and their lives. Any change requires

additional time and therefore is often not seriously considered. In

the past two decades, K–12 schools have spent an inordinate amount

of time preparing for and taking tests and trump any systemic

education changes.

-

Digital Equity:

Much data has recently surfaced showing a substantial digital divide

(the opposite of digital equity) existing between K–12 schools and

students. Both access to devices and connectivity are nonexistent or

inadequate for millions of students. Even more important are the

inequities in what students and teachers do with these devices and

connectivity (NPR, 2011).

-

Overly Myopic View/Understanding of Technology Literacy:

Schools that have a robotics club with ten students, or an annual

hour-of-code, or an eSports team do not come close to meeting our

definition of technology literacy for both the few students who

participate in these activities or the vast majority who don’t.

Schools that require all students to “do” The PowerPoint or take

keyboarding may be teaching useful but not nearly sufficient

to achieve

technology literacy.

-

Aggressive Vendors/Vendor Fatigue:

Thousands of ed tech vendors compete for a small portion of a

school’s overall budget. The larger companies aggressively market

their products to schools, and this often results in purchases not

based on research and results. Smaller startup companies with proven

products that address technology literacy have a tough time

getting-the-ear of overburdened decision makers who are deluged with

emails and cold calls.

-

Lack of Collaboration with

Students/Failure to Infuse Youth into the Solution:

This is probably the most significant obstacle to change. Schools

that deploy their students as change agents rather than the object

of change have shown greater academic and technological literacy

success. (GenYES External Research Studies, 2021)

-

Resistance to Change:

Anytime something new is needed in K–12 schools, it is generally

resisted or ignored. Countless books, articles, and research have

addressed systemic K–12 change. Major identified obstacles include

the fear of making mistakes that may well result in bad publicity,

especially in today’s social media and cancel culture. Any change

in operations causes an additional administrative load. But there is

a need to weigh the short-term cost of such change against the

larger, longer-lasting cost to society if outdated educational

practices are continued; harm can and is done when educational

practice is not updated (Tocci,

Ryan, Pigott, 2019).

Some of the above obstacles

and roadblocks have been around for decades. These mountains seem too

big to climb. Is there anything different today that can provide us

optimism in achieving widespread technological literacy as a catalyst

for systemic change? We will now suggest three significant

differences.

-

Urgency:

People are finally realizing it is time to take seriously some of

the problems the world is now facing and that present systems are in

need of change. Yes, humans have been dealing with critical problems

for thousands of years. As we are now in the third decade of the

21st century the problems have become more challenging with far dire

consequences if we fail to reform. Climate change, pandemics,

Internet hacking and misinformation, education reform, income

inequality, systemic racism, nuclear proliferation, and tribalism

are some of the urgent challenges that we must now address.

-

Advanced Technology:

Technology has been advancing for centuries, especially during the

past three decades. Technology may finally be at the point where we

can actualize bringing about the systemic changes necessary to

address the urgent problems facing humanity. High-speed networks,

cloud-based storage, artificial intelligence, robotics, etc. can now

become elements in a powerful toolkit, giving us a chance to save

ourselves.

-

Kid Power: K–12 students have always had energy and the mental prowess to

create change. All of today’s K–12 students were born in the 21st

century and are keenly aware of the urgency of the times, as they

have the most to lose if humanity fails to address the above

challenges. They have a pretty good idea of how today’s

technologies can help solve problems and don’t have to be

convinced that technology literacy is critical. We see today’s K–12 students working in powerful ways in their communities and

wanting to do more. K–12 educators are finally beginning to realize

that without the energy, expertise, and passion of their students,

reform is not possible.

Peter Exley, president of

the American Institute of Architects, recently stated that a wave of

youth activism as well as the past year’s global reckonings on

racial justice, health and inequality have made the current

generation of students increasingly insistent that their curriculums

confront a fast changing world. (Roache, 2021)

COVID-19 has shown us that K–12 schools can adapt when urgency (the pandemic), technology

(distance learning), and kid power (youth infusion) come together.

These three factors provide the background for the following modest

suggested steps that K–12 schools can do in the short-term (one to

four years) to ensure their students graduate from high school with

the technology skills addressed above and the ability to use those

skills to achieve the systemic change we so desperately need.

Suggested

Innovative Solutions for Achieving Systemic Change

Thus far, we have:

-

Made a case for K–12

technology literacy as a key catalyst for systemic change

-

Addressed current roadblocks K–12 schools experience in meeting their technology literacy goals

-

Identified three factors that

are now present that provide an opportunity to overcome these

roadblocks

Based on the authors’

experiences in achieving systemic change and current research, we now

provide some ideas to K–12 leaders (including students) on some

potential innovative solutions that can lead to universal technology

literacy. The Forum for the Future’s Nine Strategies for Systemic

Change listed above provide excellent guidance on achieving this

change. Here we will focus on Strategy 4 (Create disruptive

innovation) and Strategy 5 (Routes for them to scale).

This table lists the

challenges associated with systemic change that were discussed above

along with how each of the subsequent Suggested Solutions help

alleviate the challenge.

|

Challenge to Change

|

How Suggested Solutions

Address Challenge

|

|

Incurring a cost for

Innovation

|

All these models have youth

infusion at their core. Students receive class credit or community

service for their input and support. If they are paid, it is

typically lower wages than professional staff. This can

substantially lower the cost of change.

|

|

Tech is considered

tangential

|

Teachers integrate

technology more readily into their classrooms when they know

onsite support is available in the form of their students.

Teachers don’t have to keep up with all the tech changes as

students bring their expertise and energy to the fore.

|

|

Time intensive

|

Well prepared student

technology leaders can prepare materials for teachers, assist

peers for both online and in-school situations, provide on-demand

professional development, etc. All this saves teachers time while

allowing students to learn by doing.

|

|

Digital divide

|

All the sample solutions

reflect the school’s student diversity and one solution goes a

step further and brings diverse students throughout the nation

together that reflect national demographics.

|

|

Myopic view of tech

literacy

|

Each solution works with

teachers of all current and future subject areas and is not

isolated in “tech classes” for computer “nerds.”

|

|

Aggressive vendors

|

Student technology leaders

can be a buffer between educators and vendors.

|

|

Lack of student/educator

collaboration

|

Student/educator

collaboration is at the center of each solution

|

|

Resistance to change

|

Schools are more likely to

embrace change when they see how the change empowers students.

Addressing the challenges listed in this table also encourages

change.

|

We know that the following

solutions are not completely new but we look at them through the lens

of the three different factors identified above: Urgency, Technology,

and Kid Power.

Suggested Solution #1:

Student Technology Leaders

The Concept:

A class of 15 to 25 Student Technology Leaders (elective in

middle/high school and pull-out/club in elementary schools) is highly

trained to provide tech support to their teachers, administrators,

and staff. Student Technology Leaders (STLs) can provide another

perspective to both school administrators and teachers when it comes

to school improvement, how technology can enhance learning and

ensuring that all students are technology literate.

The Implementation:

A K–12 school delivers a year-long class where students learn the

technology available in their school. Most of the learning takes

place as they assist adults in all things related to technology. STLs

keep track of the projects they do. This STL implementation should be

a top priority because it helps administrators and teachers achieve

their other priorities.

Further Information: The Generation YES nonprofit

organization has received over $30 million in grants over the past 25

years developing this model (GenYES and Harper 2018).

Suggested Solution #2:

Youth Infusion Task Force

The Concept:

A team of K–12 stakeholders (teachers, administrators, staff,

parents, community members, board representatives, and most

importantly students in grades 4-12) form a task force to develop

strategies and an implementation model that focuses on how youth will

be involved in the issues of technology literacy and systematic

change in their school/district. This solution aims directly at the

meaningful systemic changes laid bare by the pandemic. Infusing youth

into this process also results in solving the leadership challenges

necessary to achieve urgent systemic change.

The Implementation:

A task force is established via volunteers or invitation. The task

force members attend an intensive 2-day retreat during summer or

other school breaks to lay the groundwork for creating the Youth

Infusion Implementation Model. A task force member familiar with such

a process will need to prepare for and mediate the retreat. The

retreat will result in a customised mission statement, goals,

objectives, timelines, milestones, and next steps. The Task Force

meets periodically to create drafts, solicit feedback, publish a

working implementation model, monitor progress, and revise as

necessary. Such activation of youth power is consistent with GenYes

and Sally Uren (2019) Forum for the Future models for success.

Further Information:

The definitive resource for K–12 students working with adults on a

task force, school board, curriculum committees, etc., can be found

at the Youth Infusion website (Lesko 2021).

Suggested Solution #3:

After School For-Credit Learning

The Concept:

In this solution, middle and high schools require each student to

participate in one or more online or onsite after school learning

activities related to one or more of these three learning topics --

youth leadership, systemic change or achieving technology literacy.

The Implementation:

A committee of stakeholders (including a substantial number of

students) determines the minimal amount of time these learning

activities must take to meet this requirement. The committee can

provide a list of acceptable learning activities that could include

online courses, community service projects, internships, existing

school and community based learning opportunities, etc.

Students in the school can

also suggest other learning activities that could meet this

requirement by submitting a proposal that addresses one or more of

the learning topics. In this case, the committee would create a

proposal application for the student to submit to the committee. The

committee would then determine whether to accept, reject, or modify

the proposal.

The committee would also

decide whether an artifact will be required to receive credit for the

learning activity. Artifacts could include videos, podcasts, recorded

webinars, social media posts, websites, digital presentations, oral

presentations, etc. Exemplary artifacts can be posted on the school

or district’s website as examples for future after school learning

activities.

Further Information:

This solution is basically a required after-school onsite or online

course. The literature is rife with information on this learning

methodology. The Aurora Institute is a leader in this field and has

many useful resources (Aurora, 2001). The uniqueness of this solution

is that it is a strategy specifically addressing technology and

systemic change. Estonia is a country that has a similar requirement

for every student taking after school classes in their Hobby Schools.

(Hatch, 2017)

Suggested Solution #4:

Local Required Systemic Change Class

The Concept:

A half or whole day each week is dedicated to every middle and/or

high school student attending a Systemic Change Class. Every student

will take and every teacher will teach the same class. The class is

divided into six 6-week learning modules. The first module addresses

technology literacy and the remaining five each address systemic

change issues in education, health, economy, environment, and

justice. Each class will be randomly selected from the entire school

population stratified to ensure, as much as possible, an equal number

of students from each grade level and gender. Teachers will have

access to some resources related to each topic but they can teach the

class as they see best matches their academic interests. For example,

a history teacher would look at each systemic change module through a

historical perspective, an art teacher through art that reflects each

system, a math teacher through statistics and graphs, a coach through

health and fitness, etc.

The Implementation:

Much of this and the following Suggested Solution’s preparation and

delivery of this Class depends on the teacher. Some professional

development and guidance will be provided but trust must be given to

teachers, all who have college degrees and subject area expertise.

There is no prescribed learning here. Teachers address critical

issues using their creativity. Having every teacher in a school teach

the same Systemic Change Class from their perspective ensures that

students relate systemic change and technology literacy to all

subject areas and their daily lives. Of course, the students

themselves should be part of determining the module’s direction and

what learning will take place. If a school has a student technology

leadership team (Solution 1 above), these students can be distributed

into each class to provide technology support.

The first Systemic Change

Module addresses technology literacy and centers both on the

technology they will need to use in this course, as well as

technology’s effect on society in general and five Systemic Change

Modules that follow.

Each module will include the

production of one artifact that summarizes what the class did and

learned. This artifact can take many forms (videos, websites, music,

podcasts, infographics, slideshows, graphic arts, etc.). The only

restriction is that the artifact has to be available to share on the

school or district website. At the end of the school year, a school

with forty teachers will have created 240 artifacts from 240

different Systemic Change classes.

Further Information:

The previous three Suggested Solutions are based on rigorous research

studies and a long history of successful implementations (GenYES,

Youth Leadership, and after-school learning). Of course linking these

strategies to technology literacy to systemic change makes all these

solutions unique. This Solution #4 and its related Solution #5 have

little historical research. Requiring a K–12 student body to take a

substantial amount of time each week to discuss topics of national

concern and urgency is in its infancy. Spain, Italy, and the

Netherlands are in various stages of such a model as it relates to

climate change (Roache 2021 and Coelho 2018). Given the premise of

this article, the timing may be right to engage in a major research

grant to study the efficacy of such an approach.

Suggested Solution #5:

National Required Systemic Change Class

The Concept:

This solution is similar to the the previous Suggested Solution #4.

The difference here is that the Systemic Solution Class is made up of

students in multiple schools from multiple states; students connect

virtually across these different geographic locations. Diversity is

added to Solution #4. The teacher and student makeup of each class

will come from urban, suburban, and rural schools resulting in a

racially diverse class. A major reason for systemic inequality is

that the majority of schools serve students in their racially

segregated neighborhoods. This model takes into account the present

day urgency for systemic change and uses technology to bring

different perspectives into the Systemic Change Classroom.

The Implementation:

This is much the same as Suggested Solution #4 except that putting

together the classes is more complicated. Participating schools must

be carefully selected so they are as diverse as possible. Anywhere

from four to ten schools would work. Each school would submit a list

of students who would be participating along with their grade level,

gender, and race. Once this information is obtained, the students are

distributed in the most diverse manner possible. Each Systemic Change

class would contain at least two students that attend the school

where the teacher is located. Once the class is created, it operates

the same as the localized version of the model.

Here is an example of how the

selection process would work. Ten nationally diverse schools submit

their participating student and teacher names. In this example let’s

assume that the total number of students is 5,000 (average of 500 per

school) with 250 teachers (average of 20 students per teacher/class).

Larger schools would end up with more students from their own school

in their classes and vice versa. At least two students from each

school will be enrolled in each class in that school. This ensures

that each teacher has two students to assist them with all aspects of

the class. Each of the 250 teachers will receive their class lists

prior to the start of the school year. These 250 classes will produce

1,500 Systemic Change artifacts.

Further Information:

See Suggested Solution #4 above

Conclusion

Keeping our formal education

spaces updated to equitably prepare students for the times has always

been a challenge in schools. Technology advancement, alongside

current pandemic public health safety protocols requiring -- at least

partially -- remote instruction, has made the educational space ripe

for adopting a more holistic, innovative use of technology within the

classroom to better prepare a 21st century citizenry. Yet, we know

that to maintain the relevance of these technologies, kids themselves

need to be empowered within the classroom’s adoption of technology

to sustain these efforts. Put another way, youth should be infused

within

technological literacy endeavours to actualize systemic change.

Further understanding of technology-enabled participatory

instructional modes in formal education is needed for change.

Relatedly, educational research is needed to understand how students

empowered in this way learn not just the course material but

fundamental collaborative and communicative skills necessary in

today’s world.

Technology literacy is more than knowing how

to adeptly move across various devices or use these devices to create

digital content; it is also understanding how

to be a responsible

citizen of an online, interconnected society both locally and

globally. Our world demands much of our young people: knowing what

online information is valid, keeping up with changes in technology

and digital outlets, being able to communicate their own needs across

a myriad of platforms. Is it time for young people to demand

classroom experiences to enable lifelong learning? It is the

intention of this article to synthesize the lessons learned from the

past forty years to guide classrooms in empowering youth to be

digital citizens in a world that demands it. Increasingly, schools

require more information about the complex in-real-life and digital

learning ecologies that they inhabit. To this end, researching how

technology-enabled digital spaces interrelate to school settings is

critical; with this knowledge K–12

schools can ensure their students are prepared to use technology as a

catalyst for systemic change moving forward.

Bibliography

Aurora Institute. “A New

Dawn for Every Learner.” Aurora

Institute,

https://aurora-institute.org/. Accessed 10 May 2021.

Coelho, Andre. “Amsterdam,

The Netherlands: Donut-D-Day.” BIEN

Monthly Bulletin,

BIEN, 25 September 2018,

https://basicincome.org/news/2018/09/amsterdam-the-netherlands-donut-d-day-conference/#:~:text=On%20September%2015th%202018,inequality%2C%20and%20unstable%20financial%20systems.

Accessed 5 May 2021.

Connolly, Mark. “What does

systemic change mean to you?” Accelerating

Systemic Change Network,

ASCN, 1 February 2017,

https://ascnhighered.org/ASCN/posts/change_you.html. Accessed 7 May

2021.

Cox, Tony. “Closing Digital

Divide, Expanding Digital Literacy.” National

Public Radio, Run

Time: 7:46 ed., 29 June 2011,

https://www.npr.org/2011/06/29/137499299/closing-digital-divide-expanding-digital-literacy%E2%80%9D.

Accessed 26 March 2021.

Dictionary.com. “Catalyst.”

Dictionary Entries,

Dictionary.com, 2021, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/catalyst.

Accessed 26 March 2021.

GenYES. “GenYES External

Research Studies.” GenYES

Research Studies,

Youth and Educators Succeeding,

https://www.genyes.org/genyes-research#academics. Accessed 9 May

2021.

Harper, Dennis O. Principal's

Guide To Student Technology Leadership.

Olympia, Generation YES, 2018.

Hatch, Thomas. “10 Surprises

in the High Performing Estonian Education System.” Thomas

Hatch, 7 August

2017,

https://thomashatch.org/2017/08/02/10-surprises-in-the-high-performing-estonian-education-system/.

Accessed 23 May 2021.

“ISTE Standards for

Students.” International Society for Technology in Education, 2016,

https://www.iste.org/standards/for-students. Accessed 2 April 2021.

Lesko, Wendy, and Youth

Infusion. “Welcome to Youth Infusion.” Youth

Infusion Strategies,

https://youthinfusion.org/. Accessed 5 May 2021.

Roache, Madeline. “Climate

101.” Time

Magazine [New York

City], no. Volume 197, Numbers 15-16, 4 May 2021, pp. 80-84.

Stein, Zachary. Education

in a time between worlds: essays on the future of schools, technology

& society. 1st

ed., London, Bright Alliance, 2019.

“Technology Literacy.”

Glossary Index,

Top Hat, 2021, https://tophat.com/glossary/t/technology-literacy/.

Accessed 2 April 2021.

Youth and Educators

Succeeding. “Generation YES Website.” Youth

and Educators Succeeding,

2021, https://yesk12.org. Accessed 5 May 2021.