New Survey Suggests Teacher Roles Post-Lockdown are Unsustainable, Expectations Need Re-evaluating

Schools are back in-person, but that doesn’t mean things are back to normal, according to our latest survey of 685 K–12 teachers from over 500 school systems across 49 states. The full report on the survey, which also includes responses from nearly 400 K–12 administrators, is available at our website, ChristensenInstitute.org.

Since fall of 2020, the Clayton Christensen Institute has been conducting a series of surveys to collect snapshots of instruction and the perspectives of teachers and administrators as U.S. K–12 schools navigate the COVID-19 pandemic. During mid-April to mid-May of this year, we gathered 1,042 responses from a nationally representative sample of teachers. In October, we ran another round of data collection.

We’re just beginning to process and analyze this data, but as we dive in, some of the most striking findings relate to how teachers are handling the current challenges on their plates. In many ways, their roles seem unsustainable. Is it time to rethink some of the core approaches to K–12 schooling?

Teachers are facing new struggles

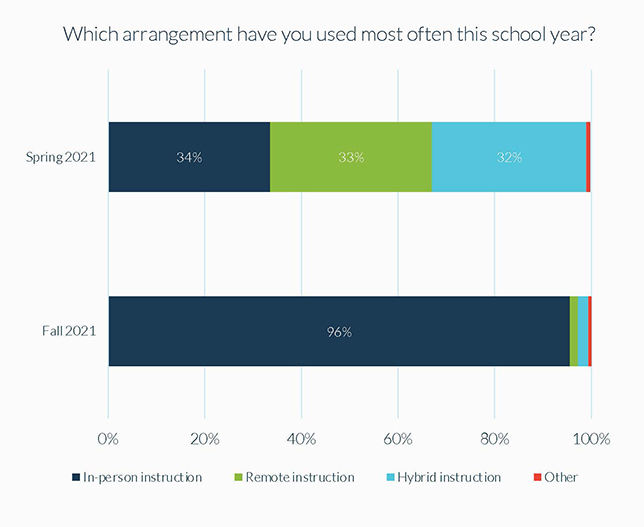

Teachers’ circumstances have shifted dramatically. Whereas survey results from last spring revealed that most teachers spent the school year primarily in remote or hybrid arrangements, this school year nearly all teachers are back to teaching in-person, as shown in the graph below.

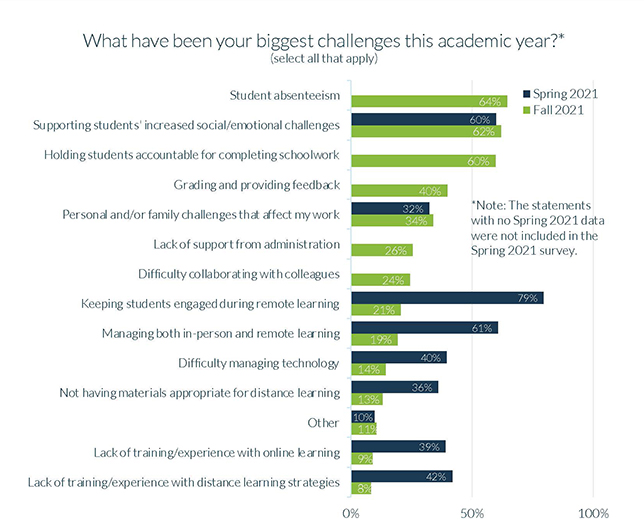

As teachers’ circumstances have changed, so has the nature of their struggles. The next graph shows the proportion of teachers who identified various challenges as relevant to their experience.

What hasn’t changed for teachers?

While our latest survey reveals how much has changed for teachers since the last school year, it’s also worth noting what hasn’t changed. The extent to which students’ social and emotional difficulties from the pandemic affects their classroom, for example, is virtually the same. Last spring 62% of teachers identified this as a challenge; this fall 60% did.

Some might have expected a decrease, now that school is back in-person. But returning to a more familiar setting hasn’t meant challenges from the pandemic aren’t seeping into the classroom. One teacher noted, “I am surprised by the major social/emotional problems the 4th and 5th graders are having. It’s almost as bad as a Pre-K student when they first start school and cry for their parents. I’ve had 4th and 5th graders break down crying saying they want their mommy.”

What are teachers’ biggest challenges right now?

Even with most schools returning to in-person instruction, major struggles caused by COVID-19 remain. One of the most pervasive challenges teachers noted in our latest survey was student absenteeism (64%). COVID presents logistical challenges, with one teacher explaining that “It is also next to impossible to determine who is chronically absent and who is quarantined until they return which makes holding students accountable for assignments difficult.”

An equally prominent challenge for teachers has been holding students accountable for completing schoolwork (60%). As teachers push to reach academic benchmarks, several referenced the temptation that others have to use COVID as an excuse to lower the bar. As one teacher noted, “Parents and school districts are continually talking about how ‘difficult’ this is for our students and giving them free passes which do not help the students but enable them to use the ‘cop out’ of ‘I am a covid kid’.”

What else seems challenging?

A resounding chorus of comments in the free-response section of the survey brought to light two major challenges that we did not ask about explicitly in the survey: 1) student behavior relative to the norms of school, and 2) teacher stress, exhaustion, and capacity overload. For instance, one teacher shared that “Students have forgotten how ‘to school’ … They forgot how to deal with deadlines, time management, and what it was like to show up to the building 5 days a week.”

Another teacher’s comments typified recurring statements about workload:

“We are short staffed in every possible area from bus drivers and custodians to teachers and principals and therefore constantly losing planning time to cover someone. This leads to ridiculously long hours when the planning and grading must now be done 100% on our time most days. Teachers are more exhausted and burnt out then I have ever seen before and leaving the classroom in droves making the situation even worse. Unfortunately, it is impossible to keep all the balls we are juggling in the air all the time and important things are slipping through the crack more often than we are comfortable with.”

Should schools and educators rethink expectations?

Altogether, the data from our latest survey raises an important red flag: even with the shift away from remote learning, teaching is exceptionally challenging right now. Interestingly, however, these challenges are rooted not in threats to health and wellbeing, but in expectations.

Policy makers and society expect schools to ensure that students meet certain markers of academic achievement at each grade level, but after more than a year of shoddy remote instruction, many students are off track. Teachers expect students to follow certain behavioral norms for conventional instruction to function, but after 18 months of unconventional schooling compounded by stress and social isolation, some students aren’t conforming.

In light of these challenges, one temptation is simply to lower expectations. But this is a dangerous proposition, especially when expectations are often lowered most for the most disadvantaged students, to their detriment. Yet at the same time, expectations disconnected from reality make a recipe for failure.

Making K–12 education holistic and sustainable

What education needs right now is a re-evaluation of expectations.

Our society needs to broaden its narrow focus on test scores to look more holistically at all the factors that affect student success and long-term thriving. One way to keep students on track to success might not be doubling down on acceleration with a side dose of remediation, but instead figuring out how to do mastery-based learning.

To get students re-engaged and motivated to learn, perhaps the answer is not conformity to the norms of conventional schooling, but rather shifting to more student-centered instruction that taps into students’ interests and intrinsic motivation.

And perhaps the solution for students’ social and emotional challenges is not just social and emotional learning strategies, but rather offloading some basic instruction to mastery-based, self-paced online learning so that teachers have more time and capacity to nurture supportive relationships with their students.

My fear is that if these shifts don’t come soon, K–12 education systems will break down under the load being borne by our teachers.