5 Skills That Games Teach Better Than Textbooks

Gaming offers the excitement of competition and a clear promise of rewards for accomplishments. It can also help prepare students to win in the real world.

- By Dian Schaffhauser

- 11/05/14

Playing games at school can inspire students in ways that nobody could predict. For proof, just take Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone. At the very end of the story, slimy Slytherin House is celebrating its seventh consecutive win of the house championship cup — until Headmaster Albus Dumbledore rises to his feet during the end-of-year feast and hands out a generous helping of "last-minute points" to Ron, Hermione and Harry for various feats. Suddenly, Slytherin and good guys Gryffindor are each tied with 472 points. The room goes wild. Will the two houses be forced to share the cup? No. Dumbledore raises his hand for silence and pronounces the memorable line, "It takes a great deal of bravery to stand up to our enemies, but just as much to stand up to our friends."

The victory is decided by the modest 10 points Dumbledore grants to Gryffindor's Neville Longbottom, and with it comes a lesson worth learning: Following your conscience, even in small ways, can have a big impact. Trying to impart that lesson without the game would most likely have had as much impact as the lunch ladies making a switch from peas to carrots. Because games immerse students in a world outside their daily experience game-based pedagogy can help students learn skills that they could never grasp by reading a textbook. Here are five of them.

Connecting Physical Experiences with Learning

Some subjects are best learned through feeling them. Take the science of plate tectonics, for example. Lucien Vattel, CEO of GameDesk, a nonprofit that develops learning games and game-based curriculum, said, "Normally the way that would be taught is that a teacher would have the student review the textbook," he said. That book would use words, pictures and possibly arrow symbols to describe the invisible turmoil of the earth that happens beneath our feet all the time but at a very slow rate. The problem with a textbook is that it has only two dimensions to explain "what is fundamentally a hyper-dimensional 3D phenomenon," Vattel explained. "It's not something that happens as a still image. It happens with movement."

|

|

|

|

Extra Credit

Game-Based Learning: Not as Common as You'd Think

According to the Project Tomorrow Speak Up 2013 survey, only a third (32 percent) of elementary school teachers report using games in their classrooms. The top two reasons they give for using games were increasing student engagement in learning (79 percent) and providing a way for teachers to address different learning styles in the classroom (72 percent).

|

|

By using a game environment with simulations, such as GameDesk's Plate Tectonics, students can experience what happens when the earth's plates move, except in a dramatically speeded up amount of time. As Vattel noted, "When you experience a concept, the mind integrates that knowledge in a very different way." Plate Tectonics relies on an $80 Leap Motion controller that allows students to use hand gestures in front of the screen (not on it) to manipulate the plates to pursue various objectives set by the teacher. "Students are challenged to create mountain formations, deep sea trenches, volcanoes, island chains — and they have to understand how plate tectonics works and how the land masses and plates move under and over and across each other in order to create these different geological phenomena," said Vattel.

Just as importantly, he added, that physical experience of learning is codified in the student's brain "in a very different way than when we read something or when we receive a lecture or receive a verbal or visual representation of something."

Vattel recounted an experiment in which a group of students were tested on what they learned from the Plate Tectonics activities. "We observed that when they read the question, some of the kids would close their eyes and then move their hands in the direction that they played the game in order to really make sure that they understood and had the answer right. I thought that was very powerful."

3D space is important for certain types of learning, he emphasized, in ways that could never be matched with the use of flat materials — not even a touchscreen. "A screen has a fundamentally 2D surface. You can't move into the screen; you can only move across the screen. So already the screen is now interpolating a separation from the actual phenomenon. Plates move in the 3D space; they have x, y and z directionality. The minute you are limited to the surface of the screen, you would only be able to look down at a continent and then move it with your fingers across the x and y directions. However, if you're in a completely open 3D space, you can move your hands forward, back, up down, across, diagonally — and that's connected to how 3D geological formation actually exists."

Rising to the Competition

Kristin Paolillo has been teaching full time for nine years, most recently at Joseph Melillo Middle School in East Haven, CT. Last school year she and her colleagues had the opportunity to pilot the use of Amplify tablets along with multiple software offerings available for the device, including games. And she found that whether games are played on digital devices or with small whiteboards that students hold up like junior Jeopardy players, one outcome was the same: Game-playing teaches good old American competitiveness. Or, as Paolillo put it, "how to be more on your toes, especially if you're competing against a time clock or other people in the class."

Some kids have no competitive spirit, Paolillo observed — until you get them involved in a game. Then it's every student looking out for number one — never mind those fashionable 21st century soft skills like teamwork and collaboration. "When you're going for a job, nobody is collaborating with you. They're doing what they can to get the job instead of you," she pointed out. "There's collaboration once you get the job, but you still have to have that sense of competition and that fight within yourself to get what you want. And if nobody has ever instilled that in you, you're never going to get where you want to be."

|

Extra Credit

Best Practices for Game-Based Learning

Play-test your games.

When Institute of Play works with teachers to design games for specific lessons, they encourage them to "play-test" their games with a small group of kids to look for "evidence of student learning" and to ask for feedback: "How did you like the game? How did it make you feel? What do you think you learned?" Rebecca Rufo-Tepper said that teachers "almost always say to us, 'I now realize how critically important it is to involve students in the process and really think about what they think they're getting out of it.' "

Align games with Common Core and other state learning standards.

Game-based learning is a way to support students in learning "specific and concrete goals," Rufo-Tepper suggested. "You can't have a game that's just about fun. There's got to be some kind of challenge in it. If you can take a challenge and it comes from a standard, it works very nicely."

Fit the game to the goal.

Matt Farber suggested, "Look for games that use mechanics that match up with what you're trying to teach, You don't want to shoot the zombie to solve a math problem. You want something more like DragonsBox, where it's using balance to teach algebra, because that's what algebra is."

Create an authentic learning experience.

Rather than hoping your students will remember a "bunch of facts that have no connection," advised Farber, try to find ways to bring lessons to life in ways that go beyond mere text, photos or videos. His middle school social studies classes tried out Mayan Mysteries, which puts the student into the authentic context of being an archaeologist in Mayan ruins.

Games don't have to be digital to work.

Lucien Vattel has developed games that are "high-tech," "low-tech" and "no-tech." GameDesk's Plate Tectonics fits into that first category; the second group includes games that can work on "most old PCs and don't require much technological infrastructure." No-tech games can be as simple as taking kids to an open field and letting them "explode" away from each other while pretending to be cosmic dust.

|

Working as a Team

Of course, as Paolillo added, working together effectively is also a skill we all need to learn. But simply putting students into groups and having them collaborate on projects won't necessarily produce the outcome you'd expect. Inevitably, complaints arise: teammates aren't pulling their weight, aren't listening or don't really want to work with each other. Often the problem is that there's no structure around the team work, said Shawn Young, a high school physics teacher at Le Salésien High School in Sherbrooke, QC. "There are no roles and responsibilities. There are no accountabilities. These are all things that exist in real work teams."

Of course, as Paolillo added, working together effectively is also a skill we all need to learn. But simply putting students into groups and having them collaborate on projects won't necessarily produce the outcome you'd expect. Inevitably, complaints arise: teammates aren't pulling their weight, aren't listening or don't really want to work with each other. Often the problem is that there's no structure around the team work, said Shawn Young, a high school physics teacher at Le Salésien High School in Sherbrooke, QC. "There are no roles and responsibilities. There are no accountabilities. These are all things that exist in real work teams."

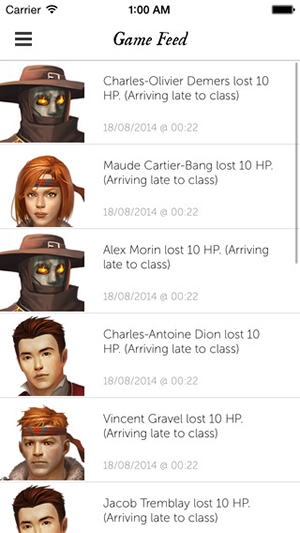

To provide that structure, Young created Classcraft, a freemium online role-playing game that works as an extra layer on top of existing curriculum. Students play in teams as "mages," "warriors" and "healers," each with unique powers, and each requiring the others to succeed.

School is a dichotomy, Young observed: both a social and an individual endeavor. "You're graded on your own. You do your own work. But everybody is in the same room living the same experience together." Classcraft is intended to provide a structure for pushing the social aspects. "It has kids helping each other who would never even talk. But because it's a game, they really want their team to do well so they start helping each other. Then it just becomes second nature. They're always in their team. The game is really built so that you can't succeed if you don't work as a team."

It helps when the teacher comes up with real risks and rewards (called "consequences" and "powers") for the teams. They can buy or lose extra test time, arrive late or receive detention, or force a teacher to sing a song of the team's choosing.

Grasping Systems Thinking

Well-designed games have an intrinsic motivation that drives players through the experience, and that persistence can be put to good use in the classroom. Take a math example: Many students have trouble working with fractions. According to Rebecca Rufo-Tepper, director of professional development for the nonprofit Institute of Play, any game that expects to replace the traditional drill-and-kill worksheet approach to fractions needs to place the students into a space where solving fraction problems is repeated, but in a way that gets "increasingly complex and ... where there's some kind of strategy involved and there's also some kind of fun and play element to it. For us, a really great game will automatically make a player want to keep playing it."

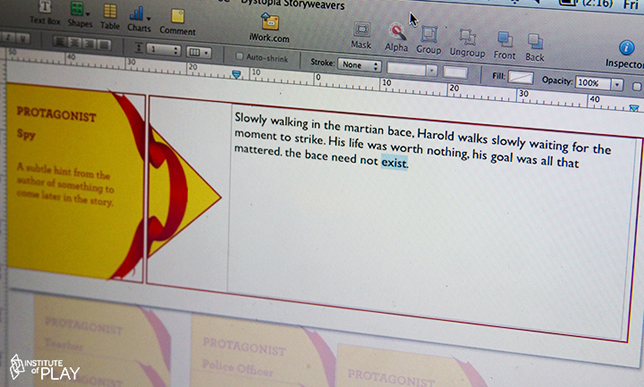

A similar approach can be used to help students practice analyzing text. Institute of Play has developed a game called StoryWeaver in which students collaborate to create a story. This requires what Rufo-Tepper calls "systems thinking," which leads students to understand the relationships within and among components. To play the game, "You start by pulling a setting card," said Rufo-Tepper. "The card says the setting is on Mars. You have to write a few sentences about the setting. You have to use a spinner to pick whether you're in first person or third person. You might write a few sentences and then you pass the story to the next partner, and they have to add in a character. They draw a character card and the character is a mouse. OK, now you've got mice on Mars. What's happening here?"

In the first round of play, the students create a story that has a character, a setting and a conflict. In the second round of the story, they go back through the story to add in metaphors, similes and edits. By the third round, "they have a pretty good draft of a story together," said Rufo-Tepper.

The game then asks the students to express how having that specific character in that particular setting affected the kind of conflict that took place, "to see the story as a system and see how all these discreet elements of the story interact. That's much more powerful than just being able to identify the plot of a story and a setting of a story," noted Rufo-Tepper. The goal, she said, is for students to understand that the story "creates this system and these things all need to align to create a coherent message for the audience. For me, that's much better to use than just having them just read through a story and answer a worksheet."

When teachers go through professional development delivered by Institute of Play, they learn a powerful assessment technique: involving students in the game-design process. Rufo-Tepper explained that after students play a game, the teacher can ask the players how the game could be made more interesting or how a rule could be added that changes how the game works. "There's something about doing that that makes them dig really deep into the process," she explained, "and it allows them to learn the content more deeply because they're changing the system of the game."

Compromise and Iteration

In Matt Farber's social studies classes at Valleyview Middle (NJ), one area that he covers is the United States Constitution. To help students experience what early Americans must have felt when they created the document, he has his class rewrite the middle school's student handbook. Students work in small teams, each assigned a category such as dress code or school dance policy. The teams do their writing virtually in Edmodo and the results are placed on WikiSpaces or Google Drive.

Throughout the day, teams in subsequent classes may rewrite what a previous group wrote. Farber said, "I have four sections of seventh graders. They all have access to one wiki. The first period might write something and it might be gone by eighth period. That can get the students enraged sometimes." And those feelings are OK, he added. "When you're designing a game, you also want to design emotions that people take away. It's not necessarily about play, it's about the emotions you want people to feel, and those emotions should be lined up with what you're trying to teach. There's a frustration in government, there's a frustration in compromise."

On the last day of the project, the students vote on whether to ratify the document they've come up with. "And they have to get two-thirds of the vote just like the Constitution," Farber pointed out. "The first year I ran this, it didn't pass. Then we talked about, 'Where do you go from there?' A couple of students complained that they were absent and didn't get to vote, and I explained that if you're absent on election day, you don't get to vote. That's the way government works."

Farber likes to point out to his students how government has elements of gaming, too. "The Articles of Confederation was the rule sheet for our government. They play tested it, and it didn't work. It was hard to use, so they got rid of it. They iterated like a designer would do and they rewrote and ratified the new Constitution," he said. "They were trying to create a better experience. That's a takeaway too. The world is not a standardized test where you take a test once. The world works by the design process of looking at the challenge, prototyping, testing and then iterating."

| You can see more great feature articles in the latest issue of our monthly digital edition. |

About the Author

Dian Schaffhauser is a former senior contributing editor for 1105 Media's education publications THE Journal, Campus Technology and Spaces4Learning.