Classroom (Re)Design for Innovative Teaching

As pedagogy evolves and classrooms move further and further away from the sage on the stage model of knowledge delivery, how can districts make sure their classrooms are supporting innovative new teaching styles? When they're lucky enough to have the opportunity to build whole new schools, how can they ensure those new spaces are fit for future generations, no matter how pedagogy has evolved?

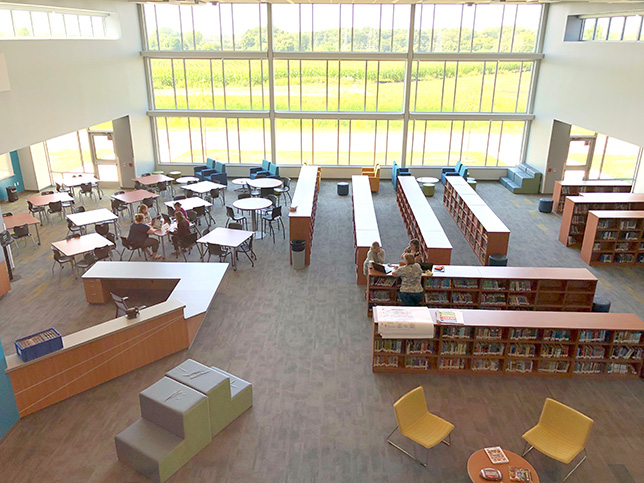

The Muskego-Norway School District has fortunate enough to try to solve both those problems recently. When they decided to build a new middle school, the answer to the second questions was, at least in part, to build a new fabrication lab — a 900-square-foot classroom with a 3D printer, laser engravers, desktop CNC machines, a Google Jamboard and a library that will act as an extension of the space.

But the answer the district found to the first question, the answer that District CIO Tony Spence gets excited talking about, was to put teachers in charge.

Resources such as furniture and technology serve to enhance instruction, not merely to create new seating arrangements.

The district began moving toward a 1-to-1 computing environment in 2013. They're currently about a third of the way there, according to CIO Tony Spence, with students in grades 5–12 using Chromebooks. But along the way they saw more opportunities to implement personalized learning, according to Spence.

They knew they would need to rethink some of their classrooms to better accommodate a new kind of teaching and learning, but instead of hiring experts to come in and tell them how to reorganize everything to fit the new model, the district decided to ask the teachers what they needed and then get it for them.

Getting the basics right — orientation, daylighting, structural grid — goes a long way toward creating schools that can adapt to new approaches to teaching and learning.

The district set up a cohort process in which they offered teachers professional development on personalized learning, and then those teachers were able to participate in a proposal process by which they could request additional resources.

"That could be furniture; that could be technology; that could be other — we'll call them consumables, like other software that requires annual subscriptions and, when appropriate, the new projection systems and the training that goes along with that," Spence explained, mentioning new Epson projectors that are being put into some classrooms as a result of a referendum.

Districts often see the building of a new school as an opportunity to embrace new ideas.

Spence said that, though final approval is up to the district office and runs through principals, "75 percent of the time it's more on the teacher to make the decision than it is anyone else."

While he did suggest that there's room for improvement in the process they developed — he said that if he had it to do over again he would limit the options to a list of approved vendors while maintaining a wide variety of options, have teachers observe other classrooms that had already implemented the ideas they were considering and avoid putting too much furniture into classrooms — Spence said the project was mostly a success.

One of the keys to pulling it off was "really keeping the focus on instruction and realizing that resources such as furniture and technology serve to enhance that instruction," and not merely to create new seating arrangements.

That idea was echoed by JoAnn Hindmarsh Wilcox, principal architect at Mahlum, an architecture firm based in Washington with a specialty in designing for education, when asked how designers can create spaces for teaching practices that will change in ways we may not be able to predict.

Muskego-Norway School District put educators in charge of making many of the decisions about furnishings, supplies and equipment in its learning spaces.

"I think the best educational space in some ways beautifully supports education but also gets out of the way," Wilcox said.

"Daylight should be present, but without providing glare or obstacles to technology in education. Flexibility in the way in which walls move or don't move should allow for different types of education to happen really fluidly and quickly," Wilcox explained. "It shouldn't be an event that the architecture is asked to be flexible — it should be part of a daily piece."

Wilcox said that getting the basics right — the orientation of the classroom, appropriate daylighting, an efficient and flexible structural grid — goes a long way toward creating schools and classrooms that can adapt to new approaches to teaching and learning.

"One of the things that I'd suggest is that as architects are laying out space they work to understand how the space might transform under different pedagogies," Wilcox added. Perhaps the "design firm can create diagrams of that same building or that same space in the different pedagogy models the district might be considering in the future and make sure that their design is flexible within those models without requiring renovation. I think that's kind of the Holy Grail."

David Mount, a partner at Mahlum and leader of the firm's K-12 practice, said that districts often see the building of a new school as an opportunity to embrace new ideas, and that experience can make clear how the classroom can get out of the way.

"Often we'll go into a existing facility where the educators want to do a lot of things, but they are limited by the building," Mount said. "To the degree that we can make things accommodate a variety of potential teaching methods and different teaching activities — that's the way that it gets out of the way."

"Often we are a catalyst," Mount said, "which is an interesting place to be because it opens up many possibilities that maybe could have been or should have been explored earlier."

Back in the Muskego-Norway School District, the district may have already hit upon a way to get their older classrooms out of the way of instruction.

"You'll see a hundred-year-old school with one classroom that you'd be shocked to see when you walk in has the general appearance and function of a nearly brand new classroom," Spence said. But more than "the stuff on casters, the stuff on wheels, the stuff that tessellates, the stuff that can quickly be moved around the classroom, the stuff that's soft spaces and textures," the difference stems from the shift to personalized learning.

"You kind of get caught up in the minutiae of it sometimes and you feel like your goal is simply to get these things outfitted and think 'build it and they will come,' but we truly did notice students responding differently when they were in classrooms that had both flexible learning spaces and choice," Spence said."

"It's not just that the spaces transformed physically," Spence said. "It's that they transform instructionally. They're being used completely differently, so when you walk in you notice that learning is different and it's not like the teachers couldn't do that without the furniture, but it certainly catalyzes that work."