6 Tips for Education Leaders Working Toward Equitable Schools

As education leaders, you are tasked with creating equitable conditions for your K–12 communities. But where do you start, and what does success look like?

My time as superintendent of East Upper and Lower Schools in Rochester, N.Y., have provided some valuable insights on how educators and administrators can make this work in their own communities. Following are six insights to help your district create schools that are truly equitable.

1. The Challenges Are Widespread

Education leaders face common challenges when it comes to creating equitable schools.

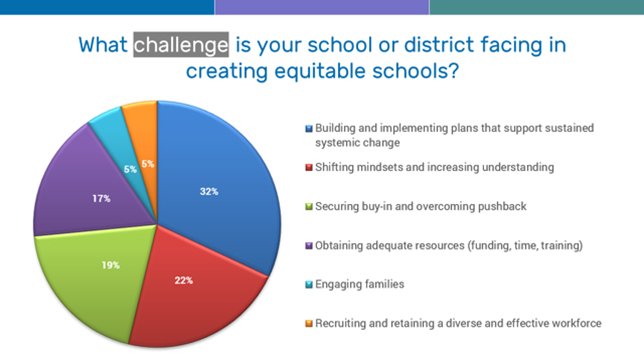

In a recent survey conducted by PowerMyLearning, school and district administrators shared that building and implementing plans that support systemic change is the top challenge they face in creating equitable schools.

Additional challenges cited by survey respondents include:

-

Shifting mindsets of stakeholders and increasing cultural understanding to meet diverse needs (22%)

-

Securing buy-in and overcoming pushback (19%)

-

Obtaining adequate resources like funding, time, and training (17%)

-

Engaging families (5%)

-

Recruiting and retaining a diverse and effective workforce (5%)

2. Start With a Big-Picture Analysis

To build a plan that is effective and sustainable, analyze your district’s processes and organizational conditions.

Prior to kicking off an equity-focused initiative, school and district leaders should take a step back to assess the conditions they have in place to support the initiative. Karen Mapp’s Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships is a great starting point for school and district leaders planning for sustainable change.

Mapp identifies essential conditions that are the nuts and bolts of any effective family and community engagement practice — and systemic change in your school or district. The Framework breaks these essential conditions down into two categories:

-

Process Conditions: Ask yourself, is family engagement linked to student learning? Are your processes culturally responsive? Be sure to focus on building relationships and collaborating with families to build mutual trust.

-

Organizational Conditions: Ensure your approach is systemic, integrated, and sustained. Family engagement needs to be visible across the entire educational system, supported by everyone from teachers to superintendents, to be effective. There must be resources devoted to the program and the program should be embedded in all aspects of education.

3. Define Your Moral Purpose Before Moving Into Action

As explained by author and Warner School of Education Professor Stephen Uebbing, “Leadership matters. The leader can shape the collegial environment and create a focus on the school’s moral purpose. The leader can help address the larger context and be certain that all children are respected and valued, at least while in school.” A former school superintendent for 23 years, Uebbing’s model of success starts with strong relational trust among the people; followed by common action; and moral purpose at the core.

Following Uebbing’s model, our district needed to co-construct and define a moral purpose before moving into action. We needed to examine what was at our core. We determined that our moral purpose is to do any and everything to ensure equitable experiences for all students, and to ensure that every student has access to all the things they need to be successful.

Once you have defined your commonly understood, co-constructed set of moral purpose and guidelines, then you can move to the action. Think about how to marry process with organizational conditions that Mapp talks about. Through this entire process, you can create and build relational trust if, as a leader, you ensure what you say you value is represented in your decisions: like your budget, the curriculum, who you hire.

Author Dennis Sparks describes “interpersonal accountability” as where people own the success and failure of their organization equally: “Cultures founded on integrity and accountability among members of the school community are attainable when leaders commit themselves to cultivating such habits in themselves and others.”

Interpersonal accountability only happens when you are anchored in the same moral construct. When you have clearly defined systems of accountability through your actions, then people will trust even they don't agree with you. Someone may not agree with your process, but they're not going to disagree with the purpose for doing it.

4. Prioritize Organizational Coherence

For those who are just starting this work, one of the first steps is to enhance your organizational coherence.

To enhance your organizational coherence:

-

Establish a common understanding of what drives the work of building teams of equity.

-

Identify systemic gaps for building coherence – the intersection of policy-practice-beliefs.

-

Establish critical next steps for process improvement.

In our first year, we took that time to interview everyone. From our conversations, we realized that there was a huge disconnect between what people told us the issues were and what the actual issues were because they didn't trust us. They told us what they thought we wanted to know. Once the trust was established, then we started to see a different level of coherence, a different level of accountability.

At that point, we were able to intersect our policy and our practices with our beliefs. If those three things aren't working in concert, then you are being performative in nature. We have to make sure we have critical next steps, not just for process improvement, but also for process accountability, process improvement and process accountability. Accountability means that the folks in the system clearly understand direction you're heading.

5. Transformation Requires Collaborating With Your Community

Transformation work is not linear; collaborating with your community is essential. When I took on my role as superintendent, the graduation rate was 29% and the dropout rate was 42%. We had one parent on our PTA, and we had a curriculum that was fragmented. We knew, based on our preliminary interviews with staff and students, that we had to redesign the entire school while also honoring the prior traditions and hard work.

We focused our attention on addressing the question, “What happened to the school?” as opposed to asking the question, “What's wrong?" The latter typically puts the blame on people while the former helps identify the root cause of the problems. Asking what happened forces you to get deeper into the historical context of the school; it forces you to unpack the true issues that are present and prevalent often through its own systemic design. More importantly, it allows you to have a sense of clarity around where you need to channel your focus and energy to address the most pressing matters.

This transformation work is hard, and K–12 leaders who undertake it are courageous and dedicated. When systems are in peril, it's often a reflection of design of that system, and not the people living in it or those who are trying to survive in it.

My team helped us “work smarter” and achieve even more. Together, we identified key levers — prioritizing those that move the needle on indicators like graduation, literacy rates, numeracy proficiency — and then asked ourselves, "Where do we start?"

It is important to remember that this work is not linear. Increasing budgets does not necessarily translate to desired outcomes.

This work is messy, too. We learned during our transformation that we needed to be patient and reflective. We learned that we must honor the parents, the students, and the staff and allow them to be co-creators in this work. We needed to come in as authentic partners and get a better understanding what the community wanted.

6. Distribute Leadership & Practice Accountability

As a leader, invest in your values. Take the time to focus on your core values and make them known to your peers, colleagues, community.

Ask yourself:

-

To what extent are your core values known to your scholars, staff, peers, families?

-

What explicitly have you done to make this known?

-

What have you structurally changed to ensure your actions are aligned with your core values?

-

To what extent did others influence your priorities? How did you know?

Distributed leadership is a proven system to hold yourself accountable and support lasting systemic improvement. Research shows a positive relationship between distributed leadership, organizational improvement, and student achievement (Hallinger & Heck, 2009; Leithwood & Mascall, 2008). The whole idea around distributed leadership is that there is never a single heroic figure; it is grounded in collective action versus an individual’s title or role.

Mobilize leadership expertise at all levels in your community to create belt systems where everyone commonly owns assessment and accountability of the system because they co-constructed it. Collectively, we can generate more opportunities for change and build capacity for improvement.